Innovation is fast becoming a tired old corporate term. But it underpins our entire financial ecosystem, and probably our human nature.

As humanity powercycles through industrial revolution, striving to do things better, the use cases for our inventions proliferate. From the starting blocks of iron mining, water mills, and steam engines, each new technology forks into a hundred new uses.

Digitisation led to the internet which led to cloud software. Radio led to mobile networks which led to 5G. Those end products are not used by one entity for one purpose, but by every industry from medicine to construction to security to education.

Thanks to those ‘building blocks’, most new products are innovations (from the Latin innovare – to renew) rather than inventions. Most startups are challenger brands taking existing systems or services and doing them better, faster, or cheaper. But even the disruptor brands who create new systems are often reiterating old ones (taxis to Uber being the clearest example).

In 2022, succeeding as a startup means finding gaps where there’s still room for innovation. Conveniently, all innovation throughout history falls into 10 broad categories that you as a startup can adopt and pursue, which we’ll explore.

But we must explore them within the context of the barrel the human race is starting down: the third industrial revolution.

The Industrial Revolution isn’t history

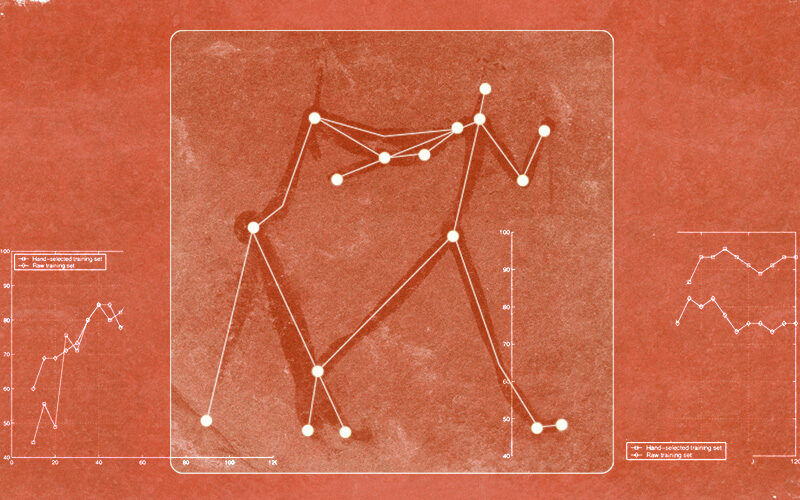

We’re all fairly familiar with industrial history – the 1800s brought water power, the 1900s brought steam engines and the great railway monopolies. But the Industrial Revolution wasn’t a singular event. It can be summed up in 6 more in-depth ‘waves’ or cycles over a period of over two centuries:

- Late 1700s: Water power, textiles and iron

- Mid 1800s: Steam power, rail, and steel

- 1900: Electricity, chemicals, combustion engines

- Mid 1900s: Petrochemicals, electronics, aviation

- Late 1900s: Digital network, software, new media

If you’ve had your coffee this morning, you’ll notice that the cycles get shorter and shorter as time goes on.

A Ray Kurzweil explains in Singularity Is Near, “Technology goes beyond mere tool making; it’s a process of creating ever more powerful technology using the tools from the previous round of innovation.” Kurzweil calls this ‘the law of accelerating returns’.

Look at computers: we used to handbuild them, now they build themselves. We don’t just improve products as we build on the breakthroughs of our predecessors – we improve the tools that make them. Then we repurpose those tools. Then those tools get cheaper (human genome sequencing cost hundreds of millions of dollars in 2004; today it costs around $600). These more accessible tools then attract a new wave of interest and investment, and new rounds of improvement and redistribution. This is where we see exponential growth, or accelerating returns.

This is how technologies we could never have imagined occuring in our lifetimes begin manifesting before our eyes. As entrepreneurs, this awards us with staggering (and kind of intimidating) potential.

As author and economist Jeremy Rifkin eloquently explains in this terrifying yet hopeful addressal of the climate crisis, all industrial revolutions have three components: communication, energy, and transportation.

In the 19th century it was the steam-powered printing press, coal, and the steam locomotive. In the 20th century it was the telephone, oil, and combustion engine cars.

Rifkin predicts the next revolution will be carried by the global IoT (allowing a sharing economy to replace centralised commerce), renewable energy, and a driverless mobility network.

This is relevant to startups because the leading communication, energy, and transportation powers of our time dictate how we live, work, and organise as a society. And they are especially pressing factors in the face of a climate emergency.

The 10 types of innovation

Despite the mad professor-esque stereotype of Silicone Valley founders, you don’t have to create a zany new innovation to bring something new and profitable to the market.

As identified by Deloitte Doblin, all innovation fits into 10 broad types. Founders can use these categories combined with an awareness of innovation cycles to target the next transformative technologies.

Profit model is the most diverse, incorporating inventive strategies that surpass basic buy-and-sell transactions: subscription models, premium/freemium, microtransactions, ad-supported revenue. Modern D2C brands like Dollar Shave Club and BloomBox have reinvigorated the milkman model, achieving a new way to deliver value and predict revenue.

Network describes modes of mergers, acquisitions, franchising, and collaboration. Startups can gain access to networks and capital by exit-strategizing from the outset.

Structure looks at how you innovate internally to overcome traditional hurdles. You might outsource staff, dropship stock, or decentralise management. You might look at how you train staff to reduce mistakes, or retain knowledge to reduce recruitment costs.

Similarly, process interrogates how you can reduce cost and waste with things like automation, localization, manufacturing formats, or even freelance staff. Manufacturing is notorious for its rigidity (limited product moulds, vast MOQs). But tech and digitization is challenging that. Toyota is famous for designing out waste with its lean manufacturing process. The fashion industry is leaning into custom or on-demand manufacturing, facilitated by cloud ERP.

At 5th and 6th are product performance and product system. Product performance is essentially: make a good product, whether through superiority, ease, aesthetic, better safety or functionality, or customization. Product system is making that product sticky, the most obvious example being Apple with its unique ports and chargers; others being DIY companies like Ryobi interchangeable tools, and fitness brands like Gymshark’s matching sets.

The 7th category is service. This is experience-enhancing perks like try before you buy, money back guarantees, loyalty programs, and finance purchasing.

Innovation in your channel looks like setting up shop in a new or more convenient way. You might go D2C where your competitors are still bricks-and-mortar. You might use pop-up or flagship stores, brand activating events or experiences, or cross-selling (placing your products strategically in other retail or event spaces).

You’ll have heard a lot about brand innovation in recent years – the importance of brand story, brand values, brand culture. It’s about standing for something, whether it’s quality, transparency, or sustainability. Co-branding and brand leverage can be part of this, especially in fashion – think Vans x Nasa or Gucci x Adidas.

The final innovation type is customer engagement. It’s kind of a vague category, based around making the user experience highly curated, experiential, whimsical, emotional, or even “magical”. Think travel and events companies like Disneyworld at the extreme end, but brands like Brewdog are finding ways to bring this into the everyday, fostering an almost cult-like sense of belonging with things like the Equity For Punks shareholding scheme.

This was a flying summary – you can read through the official definitions and their subcategories here. This is a lot of food for thought on how you can differentiate your startup without inventing a radical new Next Big Thing.

The key thing to remember is everything plays into the innovation cycle we’re currently in.

Innovation has lots of interpreted meanings (both real and imagined), but true and valuable innovation relies on adjusting to the macro environment humanity is in.

The sixth cycle will be centred around AI, machine learning, the IoT, and green tech. Taking a strong stance within or adjacent to these macro environments provides vast potential for growth.