In June, Australia came 61st out of 63 countries for ‘entrepreneurship’ in the annual IMD World Competitiveness Yearbook.

That really sucks.

To start with some consolation, ‘entrepreneurship’ was just one of over 300 assessment criteria. It was by far our worst performing category, with much better results seen in ‘economic performance’ and ‘government efficiency’ (for which we ranked 16th in both).

In overall global competitiveness, Australia ranked at number 19. It sounds better when you compare it to, say, 61. But considering our position on the world stage, our relative wealth, and the recent proliferation of Aussie-born unicorns like Canva, Atlassian, and AfterPay, why are we still so painfully far behind Denmark at number 1, Switzerland at number 2, the US at number 10, and 15 other countries?

Is a whole generation of budding Australian entrepreneurs being held back by bureaucracy, the economy, the housing market, or punishing borrowing procedures? Or does the entrepreneurial spirit just not burn bright within us?

Adapt or die… or delay

Businesses need to be dynamic and adaptable to survive. Except when they don’t need to.

Australia has enjoyed decades of comfort and prosperity. Until the mining crash of the mid 2010s, there was no need to pivot, to innovate, or to consider new economic avenues. Even if the gold runs out, we’ll still have natural gas, right?

The concept of enforced dynamism is not something we can relate to. This has left us in a stagnating mental state where, unlike America, new approaches and novel thinking are not baked into our DNA.

But isn’t everything changing now, with all this globalisation and connectivity and digitisation?

Didn’t the pandemic shake us up? Isn’t the youth of Australia, disillusioned by 9 to 5 jobs and inspired by #hustleculture chomping at the bit to lead us into a new, golden era underpinned by a flourishing knowledge economy?

Seemingly, the answer is no.

You’ve gotta want it

Peoples’ attitudes are shaped by the culture they’re born into. And Australians are held back by both pain and comfort.

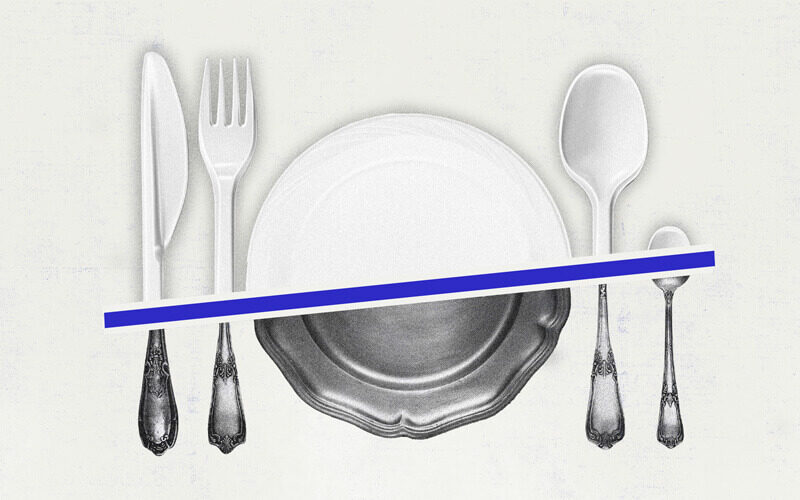

- Pain: Australian citizens undeniably have high taxes and unaffordable property to contend with.

- Comfort: Those who are (or were) able to afford property have done exceptionally well out of it. Why start a business when you can buy a house in the 1990s?

- Pain: We have an unforgiving banking system in which going into debt for a failed business endeavour can be crippling.

- Comfort: The comparatively high salaries offered by Oz do little to push us out of our comfort zones and set out on our own. Minimum wage in Australia is currently around AUD $21 per hour, whereas in America it’s the AUD equivalent of $15.82.

- Pain: The flip side to those high salaries is that if we’re not receiving them as employees, we have to pay them out as employers. And there’s little wage subsidisation for startups.

- Pain: Even to the most enterprising among us, Australia is a big old space with a sparse population. We’re roughly 80% as big as America physically, but with about 14% of the population (slash potential customer base). This also means our networks are smaller and our chances of knowing handy investors / mentors / cofounders are slimmer.

These factors have shaped our unshifting perspectives on entrepreneurship, many of which amount to “what’s the point?”.

Succumbing to the States

- Only 54% of Australians think starting a business was a worthwhile career choice, compared to 78% in The Netherlands and 66% in Canada.

- 45% of Australians think there are “good opportunities” for businesses locally, compared to 67% of Americans.

To compound matters, those who don’t see opportunities locally are quick to look overseas.

267 out of the 1000 most profitable startup cities – that’s around 30% – are in America. The 2018 Startup Muster report found that for Aussie startups, increasing sales outside of Australia was one of the most common priorities in 12 month plans, and raising capital outside Oz was a priority for 30%.

Of the few young Aussies managing to keep that self-starter sentiment alive, many are not looking to do business in their native land.

The hard truth is, America is full of people. Highly purchase-happy people at that. Looking to those green American pastures to launch or scale a startup blows your potential market wide open. And baking in a strategy for US domination will make you popular with both local and global investors.

AR/VR startup awe had US outreach baked in from the start, with one of the founders having lived there for 3 years and built strong networks with investors, clients, and developers.

EnigmaFIT shifted its attention to the US after just 2 years – founder Phillip Campbell built a solid support staff in Australia before pursuing major corporates in New York. He can credit some of that success to a partnership with FD Global Services – a consultancy dedicated to getting Aussie startups off the ground in the States.

There are not just corporate resources helping Australians hop across the pond. Our own government is complicit. Austrade, a program run by the Trade and Investment Commission, helps Australian businesses “succeed in trade and investment” by connecting them to its offices in US cities like Chicago, New York, San Francisco, and Washington DC.

It also runs a ‘San Francisco landing pad’ to provide ‘market-ready startups and scale-ups with potential for rapid growth a cost effective option to land and expand in the United States’.

Rather than stay local and contribute to the building of an Australian knowledge economy, it’s still easier and more tempting for founders to set their sights on Silicon Valley. In other words, if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.

But is this a realistic attitude for startup founders to adopt, or a defeatist one? Surely upping sticks to the States or even SEA can’t be the only options for Aussie entrepreneurs? Surely things can’t be that bad here?

To continue unpacking the phenomenon, we need to look at what’s so vastly different about Australia that perpetuates this brain drain. And if there’s one thing we make the news for regularly, it’s the wild, untamable beast that is our property market.