For every problem, there’s a startup solution (even when that problem has been caused by startups).

These startups are contributing to the startup ecosystem in two ways: by directly addressing the problems, and by leading by example. As you would expect, healthy work habits are baked into the culture.

Sleeping comes naturally until it doesn’t. Your sleep loss might be temporal – late finishes, long commutes, and/or early starts, or it might be mental – worrying, relentlessly planning, ideating, or rehearsing conversations.

It could be technology-driven – too much screentime and dopamine stimulation. And it can be worsened by our Hobbit-like indoor existences. We need time outside (in the mornings, especially) so blue morning light can hit the backs of our retinas and trigger our melatonin production. We also need a fair amount of movement to tire us out physically.

For much of this, there are simple solutions. Walking or cycling to work instead of driving. Keeping a notepad by your bed for midnight to-do lists. Less time on our phones.

But insomnia is no joke. Many of us already have healthy habits and still can’t get shut-eye. This is where tech steps in.

Many of us have smart watches tracking our heart rates and activity levels. Most have smartphones with inbuilt step, screentime, and sleep trackers. Whether we use these functions or not, we’re pretty comfortable with (or maybe increasingly apathetic to) being tracked.

We’re also sleep-deprived at epidemic levels.

COVID set off a symphony of alarm bells in terms of our mental and physical wellbeing. But the pressures of hustle culture remained. We’re starting to question that culture, focus on our health, and pay for products that help us do that.

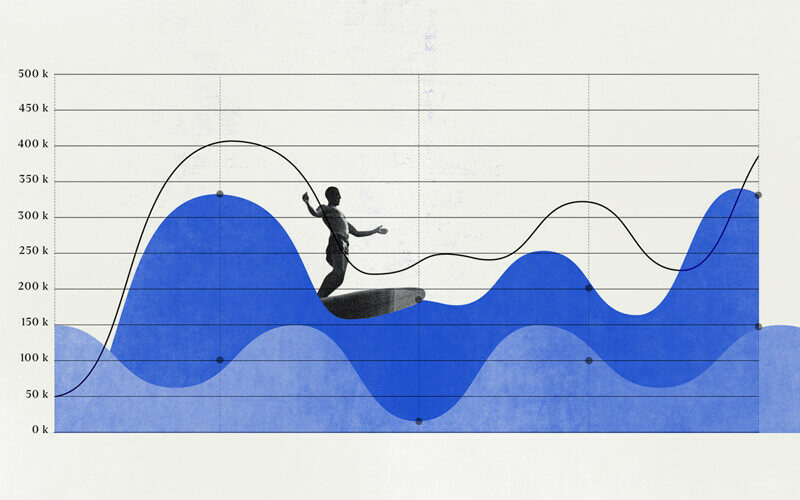

The stars are aligned for the industry built on insomnia. We’re accustomed to wearable tech, the demand is there, and the potential profits are lucrative, with the sleep tech device market predicted to grow by 17.8% to USD $40.6 billion by 2027.

Tracking our way out of insomnia

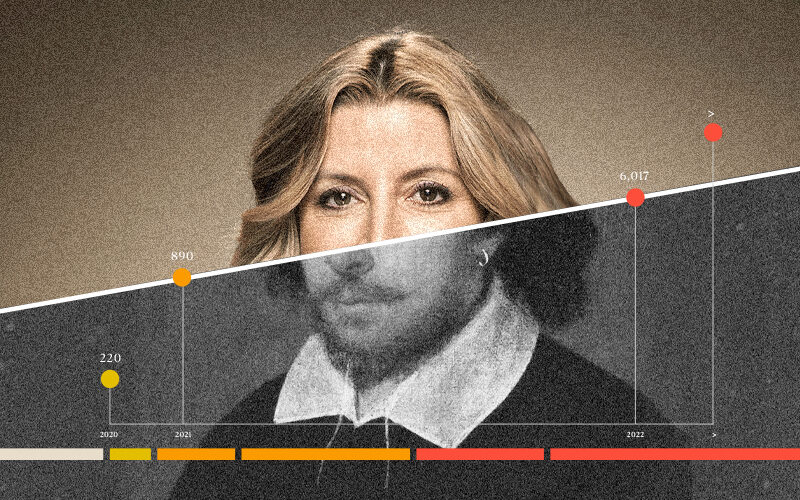

In March 2022, Oura sold its millionth ring. Oura’s model is two-pronged: a fairly steep upfront cost, and paywalled features. But healthy growth despite that and the USD $399 price tag suggests consumers aren’t shy to spend on wellbeing boosters. It’s less invasive than an Apple Watch and its battery lasts 3-4 times as long. It also claims to provide more accurate sleep-tracking due to the finger providing stronger data than the wrist.

The Muse S Gen 2 headband by Canadian-based developer Interaxon is touted as a ‘digital sleeping pill’. It’s super high tech stuff, featuring a (take a breath): “four-channel EEG system with PPG, ECG, EMG (muscle tension), and EOG (ocular movements) biosensing capabilities”.

This high-level tracking doesn’t just give you percentages to pore over in the morning, it recognizes when you’re stirring and soothes you back to slumber with music and meditations.

With a view to enter the VR market this year, Interaxon is dreaming big: “Soon, the broadly adopted technology and paradigms that we use to control and interact with our environment – and with each other – will dramatically change. Our interactions with the built environment, communications systems, entertainment platforms, transportation systems, social platforms, etc. will all be enhanced by technology that personalises our experiences by sensing, analysing, interpreting, and adapting to our arousal level, our cognitive status, and to our mood.”

Laying the old mattress market to rest

If that all sounds a little dystopian, let’s go back to something simpler – mattresses. Mattresses will always be mattresses, right?

Koala is an especially friendly example, committed to restoring the koala population devastated by the 2019-2020 bushfires. Although the new breed of mattress uses innovative fabrics like TENCEL, Lyocell, and polyurethane, their novelty lies with the model. As with Caspar, Emma, and Simba, they’re D2C. In a purchasing format that would’ve seemed unthinkable a decade ago, you don’t go and bounce around on them in-store.

It’s a surprising proposition for something so tactile. But it’s working.

It’s a rare entrepreneur that turns down a dragon’s offer, but that’s what Sleeping Duck’s founders did, choosing to bootstrap instead. Turning down half a million dollars from Steve Baxter in 2017, Sleeping Duck became Australia’s best rated mattress the following year, and is now turning over tens of millions.

Eight Sleep and their heating/cooling mattresses have developed a celebrity fanbase and raised $40 million in round C funding in 2019.

Lumping mattresses in with sleep “tech” is tenuous. But paradigm shifts aren’t always led by digital innovations. The new ‘legacy mattress’ market is defined by smart engineering and powerful copy.

Sleeping Duck’s founders Selvam Sinnappan and Winston Wijeyeratne are aerospace engineering and civil engineering graduates respectively. Their knowledge of materials (vortex-spun bamboo yarn, anyone?) is their differentiator; their knowledge of material costs their business edge.

Sleep tech is also set to be huge in healthcare. Aussie lab Sleeptite raised AUD $1.95 million in funding last year, half of which was from the government via the Advanced Manufacturing Growth Centre’s (AMGC) commercialisation fund to develop their non-invasive sleep monitoring system.

Sleeptite builds both smart tech and smart bedding for care homes and healthcare facilities to monitor biometrics, manage injuries, and improve through-the-night care.

The insomnia industry’s future looks energised, and it can do genuine good. But there are hurdles to overcome. First is the obvious irony that too much tech is part of the problem in the first place. Obsessing over our on-screen metrics means more time staring at that blue-light glare.

Second is the possibility that the truly sleep-deprived could rely too heavily on at-home devices, which are still in their nascency. Sleep deprivation is a serious condition and can lead to a laundry list of conditions like Alzheimer’s, dementia, depression, and diabetes. Sleeptech shouldn’t present as an alternative (or deterrent) to seeking out actual clinical care.

The final problem with sleep tech is getting people to actually use it. Founders tend to be in denial about pushing their physical and mental wellbeing to the limits. Many don’t think there’s a problem to be addressed, because “that’s what starting up is” and “everyone’s tired’.

Like much new gadgetry, sleeptech should be life-enhancing. It shouldn’t become a crutch, a replacement, or a shortcut to real-world remedies like working less, eating better, being active, and seeking medical advice if you need to.