When the price of land started to skyrocket in the 1880s, we started building skyscrapers.

Was using sky instead of groundspace a perfect solution? It was better than overcrowded slums. But with the social problems and safety issues, it’s a controversial subject big enough for another article.

It portends that going up instead of out may not be a magic bullet.

Hydroponics, aquaponics, and aeroponics are the practices of growing crops without any soil. They require a tiny fraction of the land used in traditional methods, and vastly less water.

Instead of growing crops in long rows that can be kilometres long, vertical farmers stack their plants on top of each other in tall towers. These towers can be indoors or outdoors, but they’re typically located in warehouses or other large buildings with controlled climates.

Victoria’s Urban Green Farms estimates:

1 acre of an indoor area offers equivalent production to at least 4-6 acres of outdoor capacity.

Vertical farms are extremely agile, able to switch up their produce in days rather than on yearly cycles.

But there’s one big problem with VF. When you’re operating indoors, how do you replace the sun?

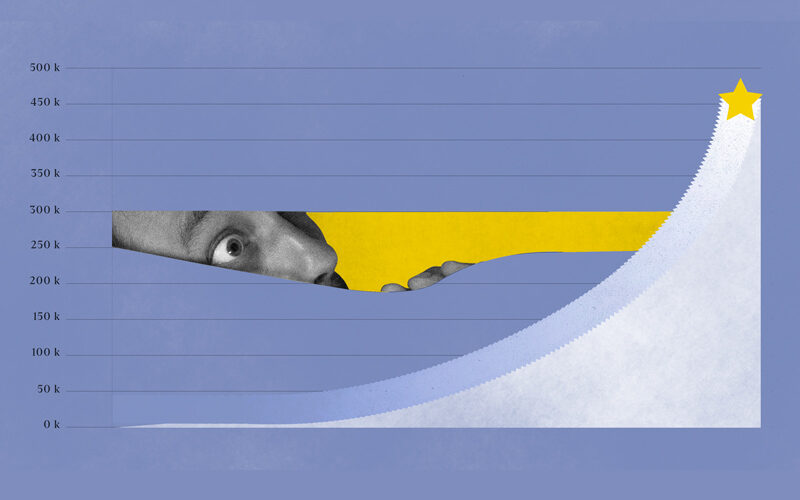

A looming crisis

Food demand will continue to rise as arable land decreases.

Australia has almost reached ‘peak acreage’ – the maximum amount of arable land that can be used for farming. The world’s population in 2050 is going to require around 56% more food than we’re currently producing. In tandem, water demand is going to increase by 55% by 2050. Over 70% of freshwater is guzzled up by traditional agriculture.

As vertical farming can feed us with a fraction of the land and and 70-95% less water, that’s hitting two criss-averting birds with one stone.

Australian weather has grown warmer and drier in recent years, making crop yields inconsistent and volatile. Vertical farms have controlled temperature, humidity, and natural light, and they’re safe from the elements, so they can provide a more stable food supply.

Plus:

- Pesticides and inorganic farming methods are no longer required in a controlled environment, making the food healthier.

- As we don’t need to transport the food as far, it’s fresher and can be delivered faster, cutting down on both food waste and mileage.

- Agricultural runoff, which is the leading polluter of rivers and streams globally, is dramatically reduced thanks to the controlled nature of vertical farming waste disposal and the lack of chemicals required.

- New jobs are generated around maintaining and operating these vertical farms. Urban centres also benefit from the sustainability and aesthetics of large-scale greenery.

And of course, humans aren’t the only ones benefiting from this innovative farming method – so are animals. We’ll be giving land back to nature and restoring natural ecosystems that have been lost to traditional farming methods.

Australian innovation

Australia already leads the world in AgTech. Several homegrown startups are indicating vertical farming could be another string to that bow.

Stacked Farm plans to inject their latest $56 million funding round into a brand-new 5000 to 7000 square metre facility to provide ‘lettuce to all’ in the face of severe shortages.

As a result of our wetter than average year, leading to flood-destroyed crops, the humble iceberg lettuce reached $12 apiece in some areas. KFC resorted to replacing the lettuce on its burgers with cabbage.

Vertical farms are particularly well-equipped to grow lettuce, Asian greens, and other leafy vegetables. Traditional farming uses 250l of water per kg of lettuce, while vertical farming uses just one. It’s expected the farm will break records for the largest output of leafy greens per square metre worldwide.

Nestled just 3km from the business suits and bankers of Sydney’s CBD are vertical farmers InvertiGro, who propose hand-in-hand partnerships with land farmers to sustainability and reliably supply them with livestock feed.

Also Sydney-based are Sprout Stack, who are able to get packaged salads onto shelves within 16 hours of harvest. VF has a huge opportunity to reduce transport emissions, capable of reducing the 2000 food miles travelled by traditional methods to just 43.

What about the sun?

It’s all very encouraging for the people, the planet, and the Australian AgTech market. But let’s go back to that one big problem: the sun.

After the initial energy used by transporting and planting, outdoor crops grow naturally under our benevolent sun god just like they have for millennia.

Vertically farmed plants still need light and energy to grow, but how can you replace or replicate a 1.4km wide fiery ball of gas?

The answer is: with a lot of energy.

Vertical farming uses 30 – 176 more kilowatts of electricity per kg of produce than simple greenhouses. That’s a huge hidden footprint that often goes overlooked.

Naturally, there are ways to combat this, like integrating a low-carbon electricity source such as solar or wind power. But the global energy grid is not quite there yet, and running warming bulbs round the clock is a pollutive energy cost.

There’s also the monetary cost.

In urban Victoria, a 10-level vertical farm would ‘cost over 850 times more per square metre of arable land than a traditional farm in rural Victoria’. And we all know how rarely prices in Victoria go downwards.

Lastly, these exclusive methods can attract a concerning type of elitism. The Oishii indoor strawberry farm made headlines with their $50 trays of vertically-grown strawberries. Michelin-starred restaurants were happy to oblige, and wealthy customers were thrilled to have access to organic, out-of-season strawberries.

But for others, it was a scary insight into the future implications of premium produce. When vertical farmers start to see dollar signs, will the “luxury” foods they’re able to grow become inaccessible to the general public?

VF is without a doubt a step in the right direction and a force for good. But the above reasons make it clear VF should complement traditional methods, not replace them.

We still need desperate action to restore the world’s topsoils. We still need to preserve water, and address the pressing energy concerns that accompany VF. Betting everything on one new technology as a cure-all is a surefire way to cause destruction in other areas.

There’s also the point that “new” farmers can learn vast amounts from traditional farmers. Growing food is still growing food. Two types of brains and two ways of working can unite to innovate.