There’s a kind of sweet irony to the state of data harvesting.

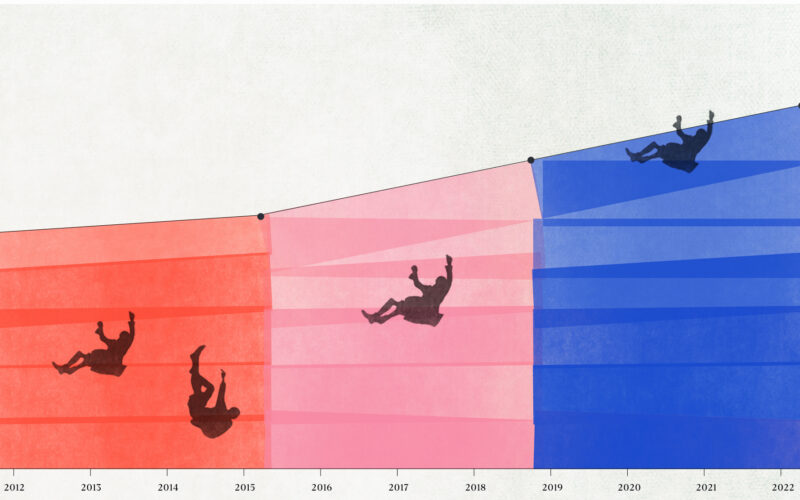

As it becomes more sophisticated, consumers become more cagey. As more channels emerge to harvest data, people find more ways to resist it.

Today, consumers are hyperaware of the amount of data companies are taking from them on a daily if not hourly basis. They know that if the service is free, they’re the product.

Qualitative data is the antithesis to big or quantitative data. The key difference is that it can only be obtained with a person’s awareness.

Qualitative data is characterised by conversation: interviews, focus groups, and reviews. In other words, words not numbers. There are no binary yeses or nos; questions are designed to be answered in sentences. It’s based on experiences and ethnography. Qualitative data is anecdotal, thoughtful, and emotional.

Pro: it can unlock complex perspectives and ideas that could never be revealed by binary responses. Con: historically, it’s been time consuming and expensive to collect, and time consuming and complicated to analyse. You can’t put conversational transcripts into a spreadsheet. You need to know what’s waffle and what’s valuable insight.

Thick vs. thin data

Champions of story-collecting, meaning-driven, qualitative data gathering, anthropologists David Geertz and Gilbert Ryle started it all in the mid-century with the term ‘thick description’. It was a way of studying people and their cultures by listening to their stories rather than processing their demographic data.

They believed thick descriptions (or thick data) help to reconnect us with the truth and meaning behind our findings.

Geertz referred to quantitative data, on the other hand, as “radically thinned descriptions”. He felt the problems with ‘thin’ data were the loss of context and the void of emotion.

In startup land, everything is small. Small customer bases, small sample sizes, and a very small communicative distance between cofounders and customers. Many founders literally speak directly to early uptakers of their service, whether at product launches and events or across social media. Processes are agile, and pivoting according to feedback is easy.

But as companies grow, so do their data sets.

An excessive reliance on quantitative and big data can lead us into the trap of “data fundamentalism”. Huge conglomerates crunching huge numbers will at some point find themselves a long way from human reality.

The truth is that people are simply too complex to be reduced to numbers on a chart.

Correlation does not always indicate causation, and massive data sets do not always show us objective truth.

Does sample size matter?

The nature of qualitative data dictates that large sample sets are not viable.

No company (or anthropologist) in the world has time to interview and cross analyse hundreds of thousands of consumer opinions in the same way that a computer can process their quantitative data.

But does that really matter?

Is it possible that the complex opinions of a hundred customers is more valuable than the impersonal, numerical data points of thousands?

This is what the term thick data seeks to imply.

Geertz wrote:

It is not against a body of uninterrupted data, radically thinned descriptions, that we must measure the cogency of our explications, but against the power of the scientific imagination to bring us into touch with the lives of strangers.

Getting in touch with the lives of strangers is exactly the mission of branding and marketing

A set of data points might tell us our target audience’s budget, location, and purchasing frequency. But it can never transport us to the heart of their pain points. It can’t reveal the social context of our customers’ desires.

LEGO is a famous example of this. In 2004, daily losses of a million dollars were calling for radical action. One theory circulating at the Danish HQ was that modern kids wanted instant gratification. They didn’t have the patience to build something before they could play with it.

A common mistake business leaders make about qualitative data is that it can’t be plotted. And it’s true that it may be harder to distil and to spot patterns within. But LEGO identified a golden goose of an idea among hours and hours of videotaped interviews with real children playing LEGO in their homes.

Patterns across location and age groups revealed a small but passionate group among LEGO aficionados. Those who liked the constructive element of LEGO play really liked it, to the point where both parents and adult LEGO fans would spend outsized amounts on sets and collectors’ items. This provided an invaluable signpost towards the profitability of brand loyals.

Netflix did the same thing. In 2020, they hired cultural anthropologist Grant McCracken to visit streamers and binge watchers in their homes.

Bearing in mind Netflix was making USD $25 billion in revenue and had 195 million subscribers worldwide, you might wonder why.

Algorithms based on quantitative data (AKA our watching/listening/liking/subscribing habits) inform our every experience of our apps. Spotify takes note of our musical tastes to deliver us album release notifications and bespoke playlists. YouTube has a ready-made list of custom ‘watch next’ suggestions on our homepage, at the end of videos, and in the sidebar.

But humans are really, really capricious. Our tastes change like the weather. And we don’t like being told what we like.

Quantitative data alone is not enough to sustain giant entertainment corporations like YouTube, Spotify and Netflix no matter how immutable they might seem.

Netflix employed McCracken to literally live with Netflix users in their homes because they knew this. They knew it’s not just what people watch that’s relevant. It’s why.

McCracken wrote about how friends, couples, and families integrated Netflix into their domestic lives. He wrote about the social/sexual code of “Netflix and chill”; about binge-watching and its increasing social acceptability. In fact, one of the key findings was that – contrary to beliefs at Netflix HQ – people don’t feel bad or shameful about binge watching. This allowed Netflix to encourage it (see the ‘binge-worthy shows’ category) rather than try to mitigate it.

The key takeaway? You’re never too big to use small data.

Don’t ask, don’t get

The amount of untapped qualitative data out there is truly staggering. And one of the obvious reasons it’s untapped is that – especially for startups – travelling the world to live in customers’ homes (or hiring a cultural anthropologist to do it for you) isn’t particularly feasible.

One Australian startup trying to bridge the gap between founders and their customers’ valuable insights is Hearsay.

Two phrases immediately jump out from the landing page: “customer intimacy” and “human truth”. In a world of cold numbers, these reassuring terms are like a balm.

Hearsay automates the qualitative process. It both teaches businesses how to build their research capability through insightful conversations, and acts as a repository for the data.

Hearsay founder Pip Stocks reminds us,

It’s not always the words used. Insight can be found in an expression on a person’s face, a picture on a wall, a sticker on a fridge, a pathway shopped, or how one product is chosen over another. It is often the seemingly insignificant things as to why customers do what they do that turns into what we call ‘wow moments.’

The truth is that everyone benefits when customers are listened to. We are no longer passive consumers but active participants. For many, brands are the closest thing they have to a community. This stuff matters, and if we’re going to build a better world, brands and their customers must be allies not enemies.

How should startups balance their thick and thin data?

As with many things, the answer is to combine both. There’s no need to throw the big data baby out with the bathwater. Factual and demographic-based data will still get you halfway there.

But big and small or thin and thick data produce different types of insights at different scales and depths. The combination of both equals real human insight. It equals better decisions. It’s how business leaders will avoid missing “that something” – that kernel of wisdom that signposts the previously obscured path to success.

It really is a whole new world of data collection. Hearsay have prepared for it with a stark awareness of growing consumer evasiveness, and a recognition of the need to bring back customer intimacy.

Platforms like this make it easier and less intimidating to shift the focus to conversational research.