Uber’s first iteration was a simple SMS system for hailing taxis. Aimed at professionals in NYC, Uber estimated its Total Addressable Market (TAM) to be USD $4 billion.

Today, operating multiple driving and delivery services across 60 countries, predictions for Uber’s TAM range between USD $300 billion and $1 trillion.

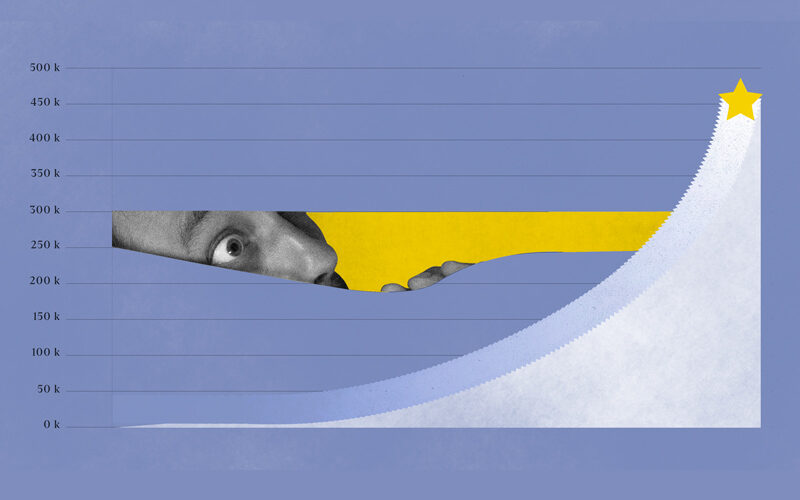

In Shopify’s early days, Bessemer’s original investment memo predicted the best case scenario was a USD $400 million exit. Even with the recent tech stock turmoil, as of July, its market capitalisation lies just shy of the $40 billion mark.

But things can go the other way when we’re talking about TAM.

When Sears was acquired for USD $11 billion by K-mart in 2005, it sought to grow the portfolio of its large off-mall stores and expand its retail empire. Fast forward to 2018, Sears filed for bankruptcy as it struggled to compete against online e-commerce giants like Amazon. K-mart had overestimated Sears’s real TAM as innovations in the online space resulted in Sears crashing from its retail throne.

TAM is the market size a company hopes to sell to (hypothetically) if they could get all of it (usually in the billions of $). Although it might be easy to assume the TAM of a product by doing a quick Google search of the industry it’s in, as you can probably tell from the above, it’s a little more complicated than that.

Is Total Addressable guessable?

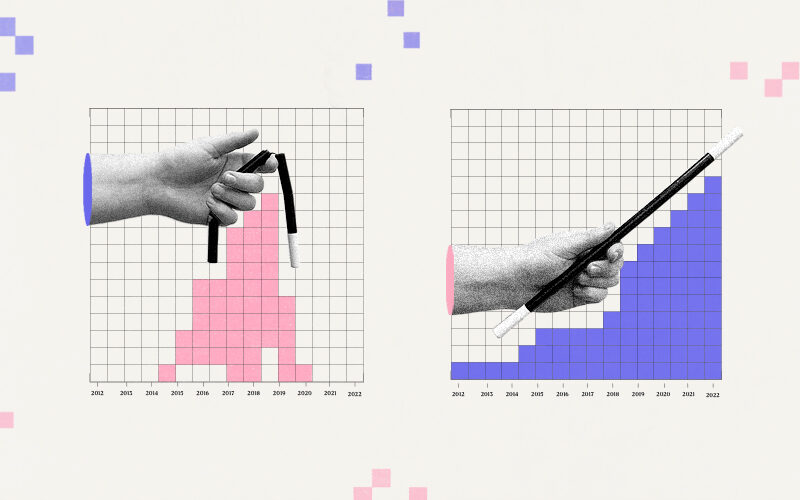

There are three main ways to traditionally identify your TAM.

The top down approach is where you’ll start by looking at the market at large, narrow it down to the portion spent on your sector, then narrow it further into your category. You might then break it down even further into things like location and customer demographics.

The bottom-up approach uses your early selling efforts to predict future growth in market sizing. The downfall is that you can easily underestimate the potential of your market. The process involves identifying your target buyer, figuring out how many of them exist, and multiplying that number by what you charge.

The value theory method is based on the willingness of buyers to pay for the product. This is often used for companies looking to disrupt a current market or form a completely new one. This method is based more on assumptions rather than data, which means the TAM can be quite unpredictable.

Although these are methods to help calculate the TAM, all three methods show a common trend between them. They are all not reliable ways to help calculate a company’s potential market share.

So why do we even use TAM?

As David Skok, General Partner at Matrix Partners, puts it:

TAM’s role in a pitch deck is to convince investors that the company is chasing an opportunity big enough to achieve venture-scale returns with the right execution.

In other words, founders think it’s a quick and easy way to show investors a feasible market for the startup they’re building.

But in reality, investors don’t really care about the TAM. They care about how big of a problem you’re solving and the growth trajectory of your business. After all, the most successful startups tackle real pain points their customers have.

A better alternative

Instead of looking at it from a market sizing potential, we need to examine it from a problem sizing angle.

To put this in a formula view:

Frequency X Intensity X Users = Problem Size

Frequency looks at how many users are often experiencing this problem (daily, weekly, monthly), whilst Intensity examines how much users are already paying for alternative solutions. Users look into how many users or businesses have this issue.

It’s not a perfect way of calculating your business’s potential dollar amount, but it helps you avoid making big mistakes in predictive exercises.

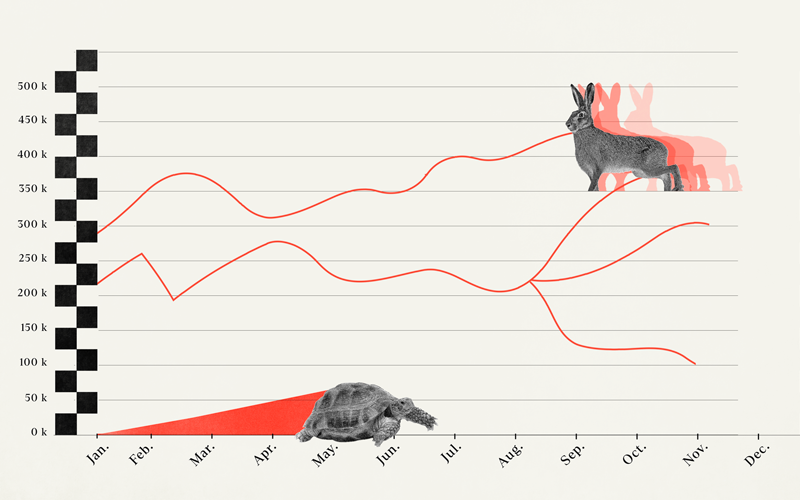

Instead of asking how big your TAM is, look into how big of a company you could build in a reasonable timeframe (say 5 to 7 years). Take into account how many customers need your product over time rather than an arbitrary number based on current legacy market share.

This method looks at the present but also future potential growth in the market. Cloud, for example, helped expand market sizing in plenty of industries where legacy players dominated for decades. Timing is everything, and new technological innovations have helped build out new markets.

This makes predicting the size of new markets tough but also gives founders an opportunity to break into exciting territories (like how disruptive Airbnb and Uber were to the hotel and taxi industry).

As Paul Graham of Y Combinator puts it:

Your target market has to be big, and it also has to be capturable by you. But the market doesn’t have to be big yet, nor do you necessarily have to be in it yet. Indeed, it’s often better to start in a small market that will either turn into a big one or from which you can move into a big one.

Solve a problem that’s likely to grow over time, and you could be onto a winner.

This means asking not just “how many companies need my product now?” but “who might need it in the next few years?”.

In short: be competitive in the present, while banking customers for the future as innovation and disruption accelerate.