How many startup founders do you know?

Given modern work culture, our extreme connectivity, and the state of the job market, it’s likely the answer is at least one. But what defines a startup?

Everyone wants to have their own “hustle”, be their own boss, or at least work in less conventional, more inspiring creative environments. The cool-factor associated with startup status is real. As a result, the term “startup” is getting bandied around to the point of meaninglessness.

Can you still attract trendy young talent by calling yourself a startup when you’ve hit 100+ employees? When you’ve been going for 5 years? When you hit unicorn status?

Semantics aside, the label has connotations that are important for young companies needing funding, and investors seeking the next big fish.

That’s precisely why the term shouldn’t be trivialised. Well-run startups can lead to exponential market expansions, significant amounts of venture capital funding, occasionally attracting the attention of a whale for a quick exit by way of acquisition, or maybe a lucrative public exit.

It’s a term loaded with meaning. So when do you need to graduate from startup status, and become a plain old “company”?

What’s in a name

Even business experts and professional investors are guilty of using vague catchall terms to define startups.

“Light and nimble”, “agile teams”, and “casual culture”. All soft descriptions without defining boundaries. SME doesn’t cut it either, because that can refer to two founders in a garage, or an enterprise with up to 200 staff members strong turning over up to $50 million.

What’s needed are harder metrics.

We need them because expanding tech firms with major funding can call themselves startups ad infinitum to dominate investor interest. SMEs can borrow the term to inject hype into job descriptions, without offering any of the usual benefits of an actual startup (like potential for growth or equity).

We need metrics we can all agree on, like years in business, number of employees, or gross revenue. Unfortunately, no one can agree on anything.

The closest logical argument for a metrics bound definition comes from a years-old article by TechCrunch+ Editor In Chief Alex Wilhelm. He argues for the criteria to be: less than $50 million in annual revenue, fewer than 100 employees, or a valuation under $500 million.

It might work, but it’s a rule Wilhelm admittedly pulled out of a hat.

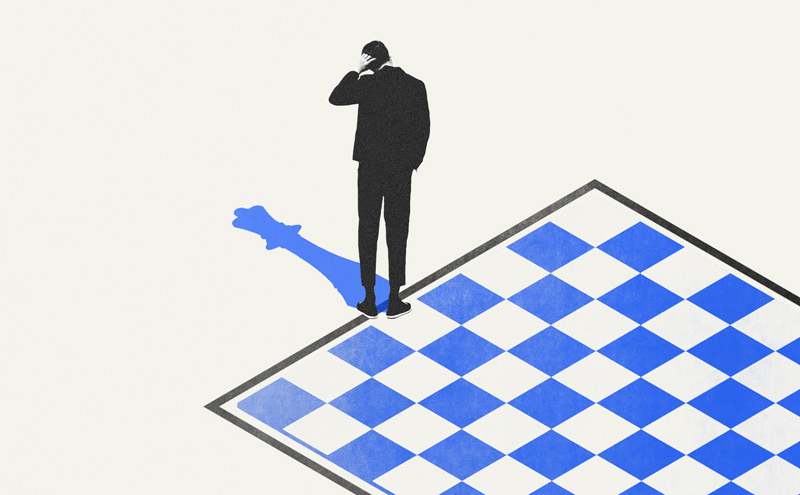

One way to think about startups without detailed metrics is that “startups” as we know them are rooted in innovation. Regular old companies essentially try to do what everyone else is doing, only better or slightly different. Startups plan to disrupt entire industries.

Does it have to be in a well-defined industry? Granted, the majority of startups seem to be in technology. It’s an area that has modern market appeal because of the rapid acceptance, integration, and market growth potential of technology products or services. But not all startups have to be based around a tech product. Biosciences also represent a great opportunity for small innovative teams to shake up the world.

Perhaps the simplest definition comes from entrepreneur and business professor Steve Blank: “A temporary organisation designed to look for a business model that is repeatable and scalable.” And as elegantly as that puts it, it still leaves us to wonder where the threshold resides for no longer using that description.

So, moving on from trying to define what it is, are there strategic advantages to hanging on to the coveted startup label?

Attracting talent

With or without a clear definition, there are very real advantages to startup nomenclature. One of the best is the ability to attract high-level talent.

In addition to exposing talented people to the cutting edge of innovation, there are several other benefits of working for a startup. You’re part of a smaller, more adaptable team. You have opportunities to take on a lot of different responsibilities, and be exposed to a rapidly evolving scene.

Jeffrey Bussgang wrote for the Harvard Business Review, “Titles, functional boundaries, roles, and responsibilities are often fluid. The team works as one, inventing, creating, moving toward shifting goals – all while working without a playbook.”

We’ve seen a huge rejection of traditional corporate life. Young talent at startups have higher visibility, their contributions are more readily noticed, the learning potential is greater, and there’s often more recognition as well as a better work/life balance.

You’ll likely also find yourself surrounded by people who are passionate about the same things that interest you, and be part of a workplace culture that’s vastly different from a big corporation.

Many people have the talent and desire to be an entrepreneur, but they just aren’t ready to take that leap. Being part of a startup, experiencing the growth of an innovative company from the ground up, watching the business brought to scale, and learning to build a unique brand, could be invaluable assets for your future. Whether the startup makes it or fails, the education is often worth it.

Attracting capital

Almost every company, young or old, needs capital. How your business is defined, as either a startup or an established company, will make all the difference regarding where that money comes from, and how hard it is to get.

Venture capital and private equity are the two primary sources of funding for most companies. Private equity firms are usually just looking for established companies that might be failing to make a profit, but could be turned around with a change in leadership and refining the operations. They buy them, turn them around, and then sell them.

Venture capital investors are looking for young, highly innovative companies with exponential potential for growth. They are willing to take bigger risks for greater rewards. They look specifically for startups.

Attractive for acquisition

The very nature of a startup is being innovative, creative, disruptive, and basically doing things that no one else is doing. When you do that, and come out of the process with a highly desirable product or service and a brand to wrap around it, then you become attractive for acquisition. The quick exit door, driving a truck-load of money.

And quite often, that was the whole point in the first place. Startups can be about nothing more than crafting a great idea into a marketable and scalable business, and then selling it.

In the end, what defines a startup might just be semantics after all.

Maybe the label is just cool and inspiring. Maybe it just means there’s lots of room for growth. Maybe it just means you’re starting something – whether it takes a year or a decade.

Perhaps the definition ends when bureaucracy catches up or your org chart starts to get real complex.

WhatsApp founder Jan Koum said: “A startup is a feeling”. But one thing’s for sure – if he tried to tell you WhatsApp was still a startup when it was acquired by Facebook for $16 billion, he’d be fibbing.