In The Wizard of Oz, the “Great and Powerful Oz” is really just a humbug behind a curtain, pulling levers to create the illusion of magic.

We can draw a few different morals from this story, but here’s one for aspiring entrepreneurs – your MVP doesn’t need to be perfect behind the scenes. It just needs to sell the magic.

There’s endless debate around the standards of quality for minimum viable products (MVPs), but it’s important to remember that the goal of an MVP is not perfection – it’s functionality. The key is to create something that gives your customers just enough of what they want so you can get feedback and iterate quickly.

But what defines the ‘minimum’ in ‘minimum viable product’? How can you create something shitty, but not disastrous; something that raises funds and publicity without draining your resources?

MVP best practices: build, measure, and learn

Entrepreneurship is a tricky undertaking for anyone with a perfectionist streak, as it requires a level of scrappiness in the beginning. Creating a minimum viable product almost feels counter-productive – but for the best final outcome, it’s nothing short of essential.

The Build-Measure-Learn approach

According to Eric Ries, author of The Lean Startup:

“The MVP is that version of the product that enables a full turn of the Build-Measure-Learn loop with a minimum amount of effort and the latest amount of development time.”

In other words, your MVP is the quickest way to get feedback from customers and learn about what they really want. It’s not about building something perfect; it’s about building something quickly so you can start learning as soon as possible.

The best way to approach an MVP is with the Build-Measure-Learn mindset. This means that you:

- Build a product based on your ideas, with just enough features to begin measuring customer engagement;

- Measure customer engagement and feedback to see what’s working and what’s not;

- Learn from your findings and improve your product accordingly;

- Rinse and repeat.

This approach is an iterative process, which means that each time you go through the loop, you should be coming out with a better understanding of your customers and a more refined product.

The Ready, Fire, Aim model

Michael Masterson’s book Ready, Fire, Aim is nightmare fuel for perfectionists. He asserts that, rather than perfect planning, we should be aiming for a swift launch; that we should be ready to fire our product out into the world and take care of the rubble afterwards.

Masterson lists a few simple criteria your product should meet before firing, no more and no less:

- The product has enough value that people are willing to use it or buy it initially. Does it do something useful for your target consumer base that’s better than the alternatives currently available?

- It demonstrates enough future benefit to retain early adopters, meaning it totally sells initial users on the concept and has them hooked for future iterations.

- It provides a feedback loop to guide future development. This is most important – you need to instigate a feedback loop, or else risk heading in the wrong direction with your product.

Masterson’s philosophy is to get your product out there as quickly as possible so you can start learning from it and making improvements; launch now, learn later. It’s a strategy that many companies have already used with successful outcomes.

MVPs that won the day

To look at the Airbnb app and website now, you’d never guess that their first public launch was anything short of impressive. But in fact, it was downright bare-bones. Founders Brian Chesky and Joe Gebbia started out by building a tiny, rudimentary website and renting their own beds to three guests for $80 each.

The CEO of Dropbox, Drew Houston, took an incredibly light-handed approach to the demo release of his file synchronisation platform. All it took was a simple three-minute video; it was so effective that it garnered 75,000 sign-ups in the first 24 hours, and Dropbox is now a tech giant worth billions. All from a three-minute explainer video and a very ‘shitty’ MVP.

When MVPs miss the mark

Minimum viable products can be sparse and shitty – we know this now. But where is the limit? Does it exist at all? It must, because there have been many MVPs come out over the years that simply missed the mark.

An early adopter of web-based recruitment tools, Standout Jobs aimed to make talent acquisition more efficient for companies. After draining all of their resources on perfecting the first release, however, the idea tanked; they had relied on gut instinct instead of collecting user data. The feedback loop was completely neglected.

Dating websites were all the rage in the 2010s, and Triangulate had entered the scene as a data-driven solution to online dating. The idea raised an impressive $750K, but like Standout Jobs, forgot to ask for consumer input. It simply wasn’t something the target audience found useful.

When startups flop as heavily as these two examples, you can usually point to one of a few reasons:

- They failed to ask for consumer input, and didn’t create a feedback loop.

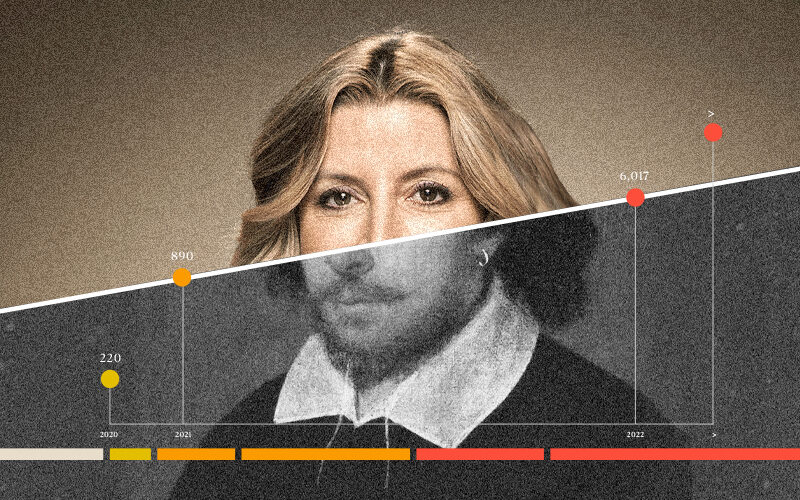

- They launched without pinning down essential details, like the viability of a machine being able to function (think about Theranos, the world-famous blood testing farce of Elizabeth Holmes).

- They didn’t solve a problem, and therefore, the idea was redundant.

- They rushed to validate a solution without considering feedback or other options.

As you can see, it’s very rarely due to the prototype being bare-bones, unfinished, or unpolished. An iPhone app wireframe with plenty of positive concept feedback is far better than an expensive, full-functioning app that its users find superfluous to their lives.

Being minimal across industries

In certain industries, the conversation around what MVPs should look like – and the level of ‘shittiness’ permitted – begins to shift. The closer you are to affecting people’s everyday lives in a profound way, the higher the stakes become.

M1 Finance CEO and Founder, Brian Barnes, spent three years learning the ins and outs of FinTech regulatory guidelines; in the lead-up to foundation, he hired a General Counsel and went through a six month vetting period to be questioned by FINRA professionals.

There were no shortcuts – nor was there any opportunity to create something ‘shitty’. But Brian himself has acknowledged that the FinTech industry is unique in this way, and for the broader entrepreneurial space, successful MVPs are subject to far less scrutiny.

Unproductive shittiness

In light of the M1 FinTech anecdote, it’s fair to say that not all industries can afford to release a shitty first iteration. But in the general startup space? Absolutely, you can. It all comes down to a few simple factors:

- Are you polishing a turd? If people don’t like your product in its most rudimentary form, they’re unlikely to buy an up-market, bells and whistles version.

- Are you wasting resources? If you’re spending too much time or money on developing features that aren’t absolutely critical to your early adopters, then you’re doing it wrong.

- Are you neglecting feedback? You should be constantly testing, measuring and iterating based on user feedback, or you’re not working toward a successful product.

The key, then, is to really think about what defines a “shitty” MVP.

It’s not about releasing something half-arsed – it’s about releasing something that allows you to learn as much as possible, as quickly as possible, so that you can serve your customers short term, and improve their experience long term.