Some startups attain greatness only by abandoning every original intention they had.

Sometimes, the right path can only be revealed through disastrous failure. The truth is, startups can run away from you. There’s no handbook, and if there were it’d get torn up anyway.

Startups exist to be different, impossible, and life-changing. In short, startups are weird.

But they also have the potential to galvanise your career, forge valuable relationships, create lifelong memories, and produce vast wealth.

How to manage the madness when you’re managing employees

Employees coming from conventional or corporate backgrounds will not know the half of it. And this is an all-too-common blind spot for startup founders who expect total devotion and understanding from the start. Many often little in return – no HR, no security, and low pay in return for a shot at blockbuster success.

Startup culture is notorious for ping pong table management (“we can’t pay market rates, but we do have beer Fridays!”) Work hard, play hard culture is a thin veil over the lack of measurable benefits and promotion potential. Startup founders can become ego-crazed and even cultish, promising to bring employees on a world-changing mission if they just sell their souls to the brand.

If you don’t want your employees to describe their experience as “like being a firefighter led by an arsonist”, read on.

Nobody knows anything

Success is much more of a lottery than people – especially experts in your field – would care to admit.

What’s the first thing you do after a lightbulb moment? You tell someone. You tell several people. Close friends and family first, potential colleagues and business mentors second. The chances everyone will respond immediately with “you’re a genius!” and a pat on the back are slim. In the spirit of brutal honesty, your peers will be quick to tell you it’s not going to work. It’s not malicious. They’re just trying to be realistic.

But in the words of famous screenwriter William Goldman, “Nobody knows anything”.

No one can predict the future. Countless founders have been laughed out of boardrooms only to end up decimating the company they were pitching to (see Netflix v. Blockbuster for a gloriously satisfying example).

Seeking advice from mentors, experts, and peers is par for the course. The trick is knowing who to listen to. What worked before may not work again. What sold a year ago may already be outdated. Even the sharpest, shrewdest, most farsighted experts cannot see 5 years into the future.

Conscious competence

As the Conscious Competence matrix dictates: “if you have no competence, then everyone with confidence will sound like an expert”.

The four quadrants of the matrix are as follows:

- Unconscious incompetence – you don’t know what you don’t know

- Conscious incompetence – you know what’s needed, but not how to do it

- Conscious competence – you know what’s needed, and can do it with conscious effort

- Unconscious competence – you’re getting things right without even thinking about it.

The key to moving up the matrix is constant learning, self-awareness, and willingness to make radical changes. But on your ascent, you’ll encounter lots of people in the first two quadrants. They might know what’s needed, and can tell you confidently, but that doesn’t mean they could do it themselves. Or, they might be a solid quadrant 1 and just don’t have a clue what they’re talking about.

Confidently spoken advice can be overwhelmingly convincing. The trick is to focus on the content, not the person. Critically analyse their viewpoints. Remove anything personal or biased. Dig down into the ‘why’ of their words. Don’t be talked out of something you believe in.

Because nobody knows anything

Imposter syndrome

Another bias you might encounter is imposter syndrome. Many startup founders present only big talk, bluster, and bravado. Inside, they feel they’re not up to the task.

It’s hard for us to convince our programmed minds – created when we were children – that we can be CEOs. Many of us barely feel like adults let alone the head of a company. At startups, it’s common to be a young person hiring other young people. A frequent stumbling block for prodigal bright sparks is having to hire and manage employees ten or twenty years their senior.

But employer/employee dynamics are shifting.

The HiPPO effect

Hierarchy is natural in the animal kingdom. It’s been present in workplaces since workspaces began. Thanks to the way our brains work, and the authority bias we’re all susceptible to, we tend to look to the Highest Paid Person’s Opinion to make the final decision.

But the HiPPO might not know best.

Letting your employees make decisions by themselves and with other colleagues will produce more creative thinking, more room for expression of ideas, and increased confidence in their abilities. Practice taking the role of observer in meetings. Hold Q&A sessions. Reward expressive employees with positive feedback. Foster collaboration, not control.

The four quadrants of Radical Candour

There’s a way around these tyrannical cognitive biases that throttle the potential of so many workplaces. You might call it a pathway for startup founders to both grow as individuals and cultivate confidence in their employees. But you might not like it.

Allow your employees to challenge you. Encourage brutally honest feedback. Nourish a culture of radical candor.

In the work-from-home era, relying on Zoom, Slack, and email for communication, it’s never been more important to foster a productive, challenging, and nurturing environment. Constantly assessing your own communication and management style and encouraging others to do the same will produce healthier relationships with your team, your managers, and your mentors.

It works both ways. Kim Scott, author of Radical Candour, cites ‘ruinous empathy’ as one of the biggest mistakes first-time managers make. “They fear looking like a jerk, so they don’t tell people when their work is not nearly good enough. When I was early in my career and starting a company and a first-time CEO of a software company, I got this email from about 10 of my employees. It was an article that said most people would rather have a boss who’s a total asshole than a boss who’s really nice but incompetent”.

Striking the balance between honesty and respect is a learning curve. Some steps to help you implement productive candour include:

- Remove emotion from your criticisms

- Offer constructive, reparative direction

- Acknowledge good work as frequently as you acknowledge poor performance.

It can be cruel to criticise something people can’t change. A chronically shy employee may never become a natural public speaker. A wordy person can’t magically develop a numbers brain. Before you comment, as yourself: is this something this person can actually change? If the answer is no, it’s probably not worth saying (and you might have made a bad hire).

The four quadrants in depth

Scott describes obnoxious aggression as “what happens when you challenge someone directly, but don’t care about them personally”. Feedback here might sound like, “This is an utter failure, this isn’t what the team was aiming for. Shouldn’t you measure X, Y, Z?”. This feedback challenges the recipient without being supportive.

Manipulative insincerity is when someone doesn’t care about the other personally and doesn’t care to challenge them. This creates a fertile breeding ground for office politics. Feedback here may be dismissive, insincere, or disengaged. Manipulative insincerity sounds like, “Your work’s fine, I had to make some edits but don’t worry about it”.

Car[ing] personally is a productive alternative to ruinous empathy. This is genuine praise instead of symbolic trophies and leaving employees safely in their comfort zones. It’s knowing your employees well enough to help them play to their strengths and navigate their weaknesses. It often comes in the form of helpful questions like “What environments do you work best in?”, or specific statements like “I can see you’re really skilled at X”.

Scott’s quadrant is just a framework. How employees respond to communication methods will go way back to the programming they learnt as a child. Some will respond extremely well to honestly, some will interpret it as rejection. Those used to more conventional corporate environments may be taken aback by the informal vernacular of startups. The best way to manage reactions is to simply ask your employees how they like to be communicated with.

Pitfalls of the feedback sandwich

Also known as the compliment sandwich (and in some coarser circles, the s**t sandwich) is an old-school managerial method of sparing feelings. It comprises a compliment followed by a criticism followed by a compliment. The logic at play is that the praise double-whammy will lessen the emotional blow.

There are some pretty glaring oversights in this logic. One, people hear what they want to hear. Most will leave buzzing from the compliments rather than thinking about the criticism. Two, hollow compliments are unproductive. Three, it’s an easy way to come across as insincere, and foster mistrust in your employee.

Avoiding mentor whiplash

Here’s a scenario: a highly experienced and intelligent mentor gives you a piece of advice. Then another equally experienced and intelligent mentor tells you to do the complete opposite. Who do you listen to?

Firstly, triangulate. Bring in a third, fourth, and fifth perspective.

Secondly, don’t be afraid to ask your mentors to elaborate. Ask them how and why they came to their conclusions. What real-world incident informed their viewpoint?

Some great advice is to report back to your mentors. They’ve spared their time and insight. By telling them off your own back what advice you did or didn’t action, you’re letting them know it was valued, and keeping the door open for further guidance.

Finally, remember you’re the expert. For every minute your advisor, mentor, or investor has spent thinking about your company, you’ve spent 100. If you feel in your gut you know best, you probably do know best.

Dealing with resource constraints

The main difference between startups and conventional businesses is the rapidly emptying hourglass you operate under.

Every expense has to be meticulously justified. Every major commitment is a gamble. Every big investment and market test is carried out with a horrible awareness of your runway. You’re scrabbling to create something people want and will pay for under crushing time and money constraints.

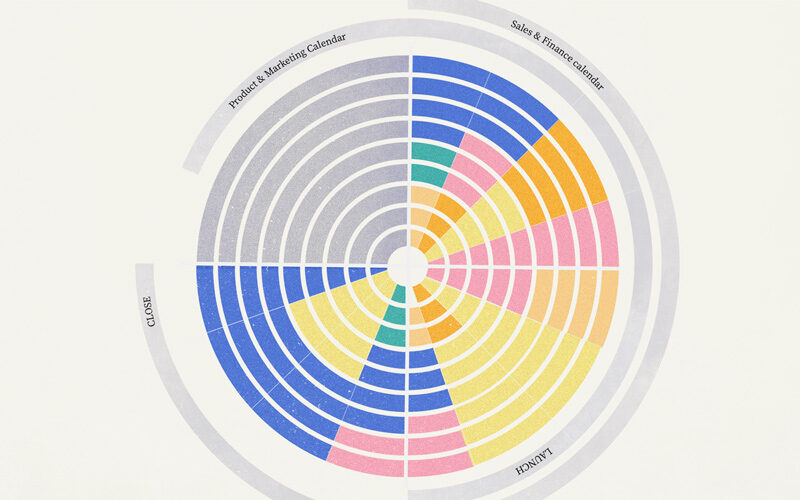

PMF and the innovation sweet spot

The ‘innovation sweet spot’ model came about in the early 2000s. It’s a simple venn diagram where desirability, feasibility, and viability overlap. This is the sweet spot for innovation. Customers want your product, you’ve got the skills and infrastructure to execute the idea, and you can afford to develop and sustain your idea long term.

The theory posits that every category is crucial. In more recent years, integrity has been added. Far from the days of tobacco companies and big oil, companies will struggle to succeed without a clear policy on conscientiousness and sustainability.

Product-market fit (PMF) occurs in the space between feasibility and desirability. There are two key ways you can work towards an optimal PMF:

- Changing the product

This can shift you between the 3 circles. Often, startups hit feasibility and desirability – the challenge is viability. For startups, fundraising challenges or burning through successfully-raised cash are two common problems. - Changing your business model

This is the only way to move towards the centre point of all categories. If you’ve got a product in demand (desirability), you’ll need to make cash flow, management, and/or Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) decisions to bring you into the sweet spot.

Complex and complicated are not the same

‘Complicated’ comes from the Latin ‘plicare’, which means to unfold. Complicated situations usually just need untangling, and then they become uncomplicated.

Complex, on the other hand, means there are many parts that don’t necessarily fit together. The Latin suffix ‘-plex’ means ‘having a number of parts’. ‘Complexus’ originally meant plaited. A multiplex houses a number of flats.

Sometimes, problems can be interweaving, but not on the basis of logic or algorithm. These are not the kind of problems that can be solved in one fell swoop, or with a singular solution.

Unfortunately, staff management is one of these complex things. Each staff member is an individual. There’s no one size fits all. The key takeaway here, according to the man who wrote the book, is to ‘manage, not solve’.

Accept you might not be able to magic the problem away, address each facet individually, and tailor your approach. As a founder, this is a sizable workload. These imperatives are the reason companies hire middle management and HR departments. Until you get there, manage – don’t solve.

Aiming for Minimum Viable Product

The purpose of building your Minimum Viable Product (MVP) is to figure out whether your “moonshot goal” is the right place to shoot for.

Perfection is the enemy of your MVP. Many founders fail to execute it because they hold out too long for the perfect build. Time and energy are wasted in development when your product could be out there turning profits. Launch does not mean the end of development.

In fact, some validation can only be completed after the product has hit the market. B2C businesses can experiment with how much they charge. Start as a base price and slowly work your way up to a higher price. Between the last ‘yes’ and the first ‘no’ is the value of your product.

If you haven’t achieved any validation from here, you might need to pivot your business into another MVP and start the validation process again. If you do find validation, your MVP development turns into iteration and refinement for further validation of that business model or product.

Your MVP is like a science experiment. It helps you to buy information. Every time you develop or iterate an MVP, you’re improving your business and operational skills.

Putting your MVP to market has only two outcomes, and both will benefit you:

- Yes, you should keep shooting for your goal

- No, you shouldn’t.

Customers lie (which is what MVPs are for)

Customers don’t know what they want, what they need, or how to express it. They don’t know what you can do. That’s why we keep our feet pressed firmly on the product release pedal. It’s the only expedient way to collect useful feedback.

“The customer is always right” is a phrase that’s misunderstood with staggering regularity. Firstly, it was not Steve Jobs’ brainchild, as it’s often falsely attributed. It goes much further back to the early days of retail when pioneering magnates like Harry Gordon Selfridge first developed conscientious customer service.

Before this, exchange of goods was conducted under the principle of caveat emptor (more commonly known as “buyer beware”, or “f**k off if you don’t like it”). Selfridge realised that sales went up when customers felt listened to. The implication was “treat the customer as if they’re always right”.

Take the phrase literally when you’re undertaking market research, and you’re gonna have a bad time. Surveying is notoriously unreliable. Focus group attendees are swayed by the viewpoints of their peers. Without money changing hands, everything is theoretical. People are simply guessing how they’d react to things.

The title of Michael Masterson’s book Ready, Fire, Aim questions the order 99% of startups do things in. Masterson’s advice is simple: “Getting things going quickly is more important than planning them perfectly.”

The only proof is in the pudding. Launch, and if they buy, you’re onto something. If they buy and dislike it, the money they’ve parted with will galvanize them to give genuine feedback. If they buy and like it, well, onto the next product.

You can never build a 10/10 product in the time and money constraints you operate under. So deliver a quality-controlled 7/10 product, and market it to the people who are delighted with a 7/10 product.

Final words of advice

If you’re reading this guide, you might be one of the many founders who started at someone else’s startup first. You get stuck in, learn on your feet, watch it implode, and move on to another startup, often with a colleague or two in tow.

If you haven’t, it might be worth considering. It never hurts to work for someone else before you work for yourself. Rinse and repeat until you’ve got a solid, trustworthy, hardworking band of startup stragglers, then set up on your own.

The right combination of people can produce a certain magic. Every now and then, it pays off in mind-boggling ways. 99% of your career-spanning efforts, experiments, and ideas might come to nothing. That extra 1% you put in can be the key to extraordinary success.

There are some factors that can mitigate the chaos. Namely: learn to fail fast. It takes time to find out what to do, but it’s expedient to learn what not to do along the way. Don’t be afraid to constantly reinvent. Stubbornness will get you nowhere.

Startups are indeed weird and wonderful things. But it’s your weird and wonderful. Change is the only thing guaranteed, and a spirit of openness is incumbent.