Did you ever see Coke ads as a kid and think, “Why are they bothering? No one’s ever gonna stop drinking Coke”.

As adults, we know that a continual cycle of advertising and innovating – AKA staying relevant – is crucial for companies to stay alive.

Companies know this too. So why do the lumbering corporate giants of the world – who’ve got where they are by doing things better than anyone else – struggle to keep the innovation cycle turning? Why are they so frequently put to shame by creative and comparatively tiny startups?

The innovator’s dilemma 101

Most innovation in business is designed to attract and retain customers. It’s a simple case of moving with the times. Innovation commonly takes existing technology and makes it a little bit better/faster/stronger. This is known as ‘sustaining innovation’.

Disruptive innovation, coined by author of The Innovator’s Dilemma Clayton Christensen, is where something brand new and niche enters the market. It’s unfamiliar and often inferior to the status quo. It starts with a small, loyal band of followers, but explodes by doing one thing (e.g. convenience, speed, aesthetics) extremely well.

Sales targets – the very requirement not just to make money but to make more money year on year – are the enemy to innovation. The tiny startups that do groundbreaking, worldchanging, previously impossible things don’t have those pressures (although they do have financial pressures of a different kind), so they have much more time to play in the sandbox.

It’s almost as if there’s more to life than profit. Who’d have thought?

But to challenge the importance of sales targets is to challenge capitalism itself (and a really easy way to piss off your shareholders).

The 5 principles (or how not to get disrupted)

So what recourse do major firms have against this impossible bind?

Christensen set out 5 principles for big corps to beware:

- Companies depend on customers and investors for resources

Companies are always chasing the tail of their most valuable customers. The vast majority don’t want new things. They want what they’re already buying on a continual scale of improvement. They will allocate resources to this rather than to disruptive innovation (AKA the unknown). - Small markets don’t solve the growth needs of large companies

Disruptive innovation must enter at the low end of the market. It won’t be appealing to the masses and it won’t command a high (or even margin-meeting) price point. One of the most important reasons big companies can’t and won’t truly innovate is because they can’t justify the risk or the inevitably low returns it will yield. - Markets that don’t exist can’t be analysed

Sustaining innovation can be based on past data and intelligent prediction. Disruptive innovation can’t be based on anything – it’s always experimental. In other words: almost impossible to justify to the board. - An organization’s capabilities reside in its processes and values

The larger a company, the more inflexible its systems. All are likely geared toward producing high-margin profits, resulting in a “computer says no” scenario for less profit-focused endeavours. - Technology supply may not equal market demand

Large companies are often so used to a) doing things well and b) competing with other large companies that they tend to overshoot. This means producing technologies people don’t want or need, so that startups can enter with a lower price point to scoop up low-end demand.

The customer is not just wrong, but inconsistent

There’s another reason massive companies lose market share to mini ones despite being aware it’s happening: disillusionment about who’s in control.

It’s always the customers (and to a degree the investors). However, there is a line, and knowing when to cross it can be the difference between sustained success and fading into failure.

Disruptive startups inherently understand this. They don’t have existing customer bases to lose. They’re much less afraid to go against the grain – in fact, going against the grain is the point.

A modern interpretation of “the customer is always right” is to give the customer what they want without bending to their will. But there are two crucial caveats that many bigger organisations have blindspots to

Listen to customer service and quality issues, but when it comes to innovation, cut the line.

Cirque du Soleil’s senior VP of marketing Mario D’Amico said it best: “Why do we want to ask what our audience thinks? We don’t care what they think. How can people tell you what they want if they haven’t seen it before? If we ask them what they want, we’ll end up doing Swan Lake every year.”

We know that people suck at responding to surveys. Even if they respond with total honesty (which they don’t), and even if they predict their future actions accurately (which they can’t), people change their minds so much their actions almost never match their opinions.

Even intelligently mined data is becoming less usable. As tech-literate consumers deliberately input inconsistent or false information (or opt out of data collection altogether), it’s predicted that 40% of consumers will be deftly dodging your marketing insights by 2024.

In short, most people don’t know what they want, and those that do won’t tell you.

A new focus on “thick” or qualitative data presents a possible antidote. That means face-to-face conversations, listening to stories and experiences, and capitalising on your customers’ emotional insights.

The customer you might need to listen to is not always your current customer.

By tailoring each new product line, advertising campaign, and branding exercise to existing customers, you’ll miss out on new customer bases and upcoming generations. And you’ll have a problem when your existing customer base dies out.

Normalise breaking up with customers

Moving away from a seemingly safe and satisfied pool of customers can be terrifying for large organisations, but when sentiments change like the wind, it’s necessary.

Gartner predicts that 75% of companies will “break up with” “poor-fit” customers by 2025. “Retain at all costs” sentiments are old hat. Retaining happy customers makes business sense, but spending time and money on offers and custom solutions for unhappy ones may become a thing of the past as companies get more comfortable with “cheers and goodbye”.

Cognitive biases play a role

Incredibly capable leaders are also capable of making incredibly bad decisions.

People in general struggle with doing two things at once, especially if we perceive them to oppose each other (e.g. chasing reliable revenue and experimenting with new streams). We’re terrible at assessing our own capabilities. We bury our heads in the sand. A whole host of human fallibilities leads even the most famed leaders in world-leading industry titans to do things badly.

The engagement/innovation paradigm

To respond to the threat of more innovative startups, large companies have a grid of options.

Option 1: Don’t engage with others, and don’t innovate internally

Going back to the Coke example: advertising keeps awareness churning and triggers spontaneous purchases. There’s the odd new flavour to keep things interesting. But at Coca-Cola HQ, the same old wheels have been turning for over a century (thanks perhaps in part to the “carbonated disaster” that occurred when they attempted a major reconfiguration). The core offering has kept its “original taste since 1886”. No disruptive innovation needed (or wanted).

Option 2: Invest in innovation, but don’t engage others

Becoming a hub of innovation may be a good option for highly technical manufacturers like pharmaceutical labs. Innovation and creativity underpin your entire operation. You won’t acquire or work collaboratively with others, but silo your team into pure product development machines.

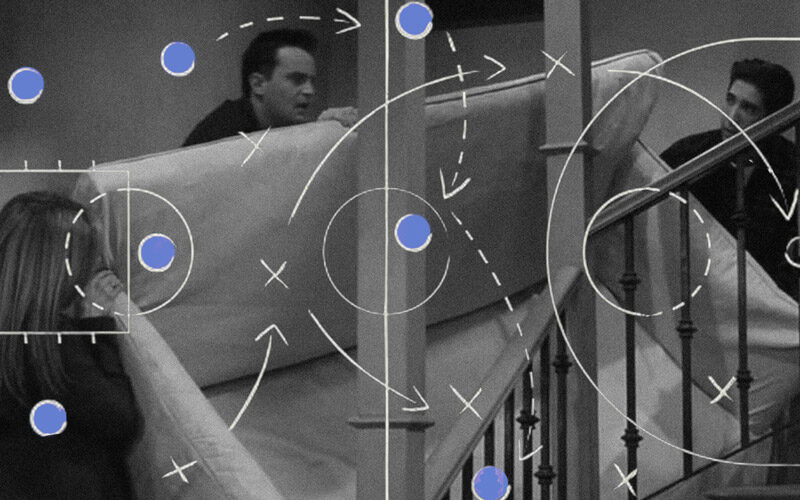

Option 3: Don’t invest in innovation internally, but engage a lot with others

Otherwise known as the “buy innovation” model, companies outsource product development, and capitalise on their operational marketing skills to bring them to consumers. This often involves acquisition of startups in which entire teams are kept on, or purchasing of IP.

Option 4: Invest in your own innovation, and engage with others

This is the partner for innovation model. Here organizations invest in and shape the innovative process, but know that they don’t have the capability to innovate alone (or see other benefits in collaboration) so they work with other partner organizations on innovation.

This strategy has been popular recently in the FinTech space where traditional banks partner with newer, more agile and technologically capable partners for combined product innovations.

Option 5: Self-disruption

Some companies do ‘disrupt themselves’, e.g. Amazon – originally a bookseller – creating the Kindle. This spawned the birth of the e-reader at the factored-in loss of book sales.

The invention of the iPad is another example of self-disruption or “cannibalization”. In fact, one of Jobs’ most notable achievements was seemingly solving the innovator’s dilemma (who else could do it?). When Jobs took over, he had the rare foresight to lead Apple away from profit focus – extremely daring at a time when the company had just 90 days of working capital on hand.

The iPad (and arguably the iPhone considering we do so little on desktop now) cannibalised the Mac to a degree. But it created value for the customer, and the obsession with this led Apple to world-leading profits despite the shift in focus.

The legacy remains. As CEO Tim Cook puts it: “the iPad team works on making their product the best. Same with the Mac team.” Do both, and do them best. Couldn’t be simpler.

The takeaway for startups

The innovator’s dilemma is a classic parable – the elephant that’s toppled by the mouse. And it’s this endemic failure that leaves a tasty portion of the market wide open for agile young disruptors to steal a sizable piece.

As well as the practical lessons for companies we’ve explored here, startups can benefit from keeping one philosophical standpoint in mind: profits aren’t everything until they are.

You will reach a point where decisions are not your own, shareholders will need to be answered to, and investors will want their returns.

Until you reach that point, hero your innovation. There’s such a thing as too small to fail.