In a move PC Gamer has called “microtransaction hell”, BMW has launched a subscription model for in-car extras across Europe, New Zealand, and South Africa.

In the UK, you can pay £15 a month for heated seats, or £10 a month for a heated steering wheel.

BMW executes this model by preloading all of the features into the car then placing software blockers on their functionality – until you pay to remove them. It’s all done remotely, so no trips to the garage for upgrades. You can change your mind anytime. And most cunningly, it allows drivers to free-trial features for a month.

The small monthly fees are more palatable than the £300 lump sum the extras would cost you together. And it’s ingenious, because who often steps back from the little life-enhancing luxuries they grow accustomed to?

Microtransactions have a short but chequered history. Some see them as exploitative, some think it’s price gouging. Some see them as a welcome convenience, or a way to enhance customizability and manage cash flow.

Could this truly be a good-for-business, good-for-customer scenario? Or are we moving towards an era where we rent everything, and own nothing?

The lead that’s never lost

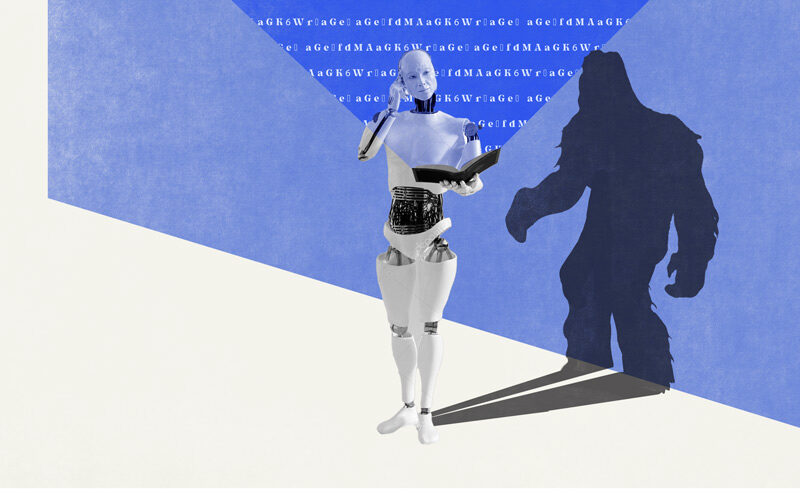

In the good old days, if you couldn’t afford something, you didn’t buy it. So businesses were stuck with customers who could afford their products. Now, thanks to subscription models, they can target buyers who can’t afford them too.

Although putting a price tag on everything feels cynical at best and money grabbing at worst, there are benefits to the customer.

No one needs heated seats year round. In Australia, we might use them for 2 months out of the year. Why pay $200 for a permanent but mostly redundant feature when you could pay $20 for the few times you use it?

Of course, the benefit to the business is just getting to see their customers happy and smiling. Just kidding.

The model will save BMW a fortune in operational costs. Why design, build, and test two different types of seats when you can build one and change the functionality with the press of a remote button? This means ordering parts at higher volumes, which in turn means much cheaper parts.

To make the model work, BMW essentially has to give every buyer a full-option car. But not only will this be priced in, but the money saved via more singular production moulds offsets the cost. Then, successful sales of “bonus” features offset them further.

Given the highly hedonic (emotional) nature of car purchasing, and the relative affordability of each feature, saying yes will be a no brainer to lots of buyers – especially those able to spend $100,000 on a car in the first place.

Even better, those who don’t commit at the dealership may well change their mind when winter comes. We can safely assume some well-timed emails will remind drivers of their open option to subscribe. BMW has cracked a code 80s salespeople would sell their souls for: the sale is never truly lost.

By providing alternative options to a cold hard cash purchase, BMW will blow their addressable market wide open in terms of affordability. And they will generate favour with investors.

Small, steady, diversified revenue streams cannot only be easily tracked and proven. Once the software is in place, countless features can be added or removed. Rich data on user behaviour can be gathered to R&D more potential streams.

Many customers will feel empowered by the choice, and pleased with the “deal”. For some, it will feel like a bitter pill to swallow. We have entrenched ideas about what “should” be included when we’re spending lots of money. You can get past the AI Driving Assistants and IconicSounds Sport packages (?). But in luxury cars, things like heated seats usually come as standard.

Having to spend extra can make us feel cheated, even if we would have paid the same overall amount under a traditional purchase model.

But we are already so accustomed to #subscriptionlife. The ecommerce subscription market was already doubling in value every year before the pandemic. We pay monthly and happily for our TV, our music, our gaming, our fitness technology, our monthly food/booze/razor/flower/toilet paper deliveries. Fewer and fewer people are caring.

Convenience champions all. As does the freedom to change our minds, and change them back as we please.

The house always wins

As much as we’d love to think everyone wins, as always, it’s the business that wins. BMW has hacked its way into reducing production costs while inflating the value of small ticket items and diversifying revenue streams.

But there is a win for the wider market, the sharing economy, and the environment.

Higher customizability means higher resaleability. People won’t have to buy brand new to get the unique features they want. They can save money and materials by buying second-hand and subscribing to their chosen features. This has hugely positive implications for the growing car sharing market.

In the case of media streaming, the same doesn’t apply. We’re already seeing what might be the slow and thunderous crash of Netflix, thanks to oversaturation of the market and subscription fatigue.

But subscription models aren’t inherently bad. If done ethically, the benefits of flexibility can apply across countless industries.