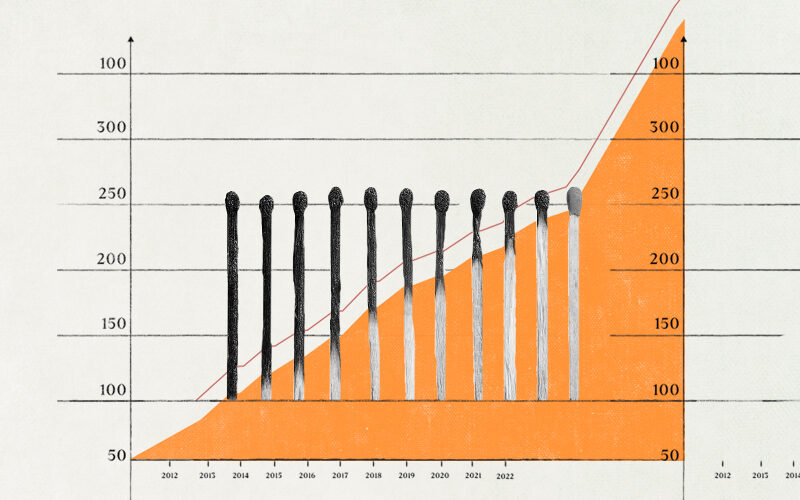

Even the most respectable news institutions have run out of formal descriptors for the Australian property market and are just calling it what it is: insane.

The pandemic made a lot of things worse and one of those things was property prices. Stimulus measures have almost been too successful. Markets across the Western world have boomed and house prices exploded by double digit percentages. New Zealand has seen 30% increases, and it’s not much better in our major cities.

Things were bad for first-time buyers after the 2008 crash, and they’re even worse now. With much of the Boomer generation settled in high value homes and upcoming generations already unable to buy them, it’s not difficult to imagine the kind of crisis we’re going to face in ten or so years. When sellers hit a mismatch with buyers, the bubble bursts.

We’re going to need some radical thinking to break us out of this rut, and not just bureaucratic policy measures that kick the can down the road.

Challengers or collaborators?

For real estate, the tech revolution that’s vowed to come for every other industry seems to have stopped short at portals. Realestate.com.au and Domain have been around for a while and serve to amalgamate listings from independent agents, just like any other comparison site. It’s pretty basic stuff.

After considerable success in the UK, Purplebricks brought the online-only format to Australia. It’s the same agent/seller/buyer format, just with no physical shopfronts, and no agent-led viewings. But we don’t love “DIY” selling in Australia – it made up just 2% of the market compared to up to 20% in the US and Canada. Purplebricks crashed out pretty dramatically in 2019. BuyMyPlace is trying to fill the gap it left, but it hasn’t been without its troubles.

Listing Loop is another hot piece of proptech that raised AUD $3.3 million in its first funding round. But it’s unclear exactly what it does differently – it’s USP is “off the market” properties, lending an air of exclusivity. But as soon as it lists a property, surely that property becomes technically “on the market”?

REALas serves as a good example of the pitfalls of a lacking personal touch. Its raison d’etre is to use local data to predictively value your house. But it can’t take into account the factors and finishes and feels of a place that make it worth that bit more than its neighbours.

Property-related startups are great at collaborating with bricks-and-mortar agents. But it seems true innovation and competitive disruption in the sector are nowhere to be found.

On the other hand…

Homely has managed to tap into something lacking without undermining the immovable object that is the high street property market. It’s attracted 10 million users so far by bringing in another party: the community.

Homely is the only real estate portal to lend an insight into what it’s actually like to live in an area through reviews, forums, and FAQs. It’s unique, it knows what its audience values, and its advertising system for estate agents has allowed it to monetise successfully.

Possibly the most promising disruptor we’ve seen so far is Patch. It’s doing something that hasn’t been done before by allowing you to “make an offer on any home – not just the ones with a for sale sign out the front.”

Patch opens up a world of potential. House prices are no longer dictated by agents overvaluing to secure sellers. It appeals to ready buyers who can’t access that exclusive pool of premium priced property that gets recycled amongst the same buyers and sellers every few years. It invites conversation and collaboration, slotting right into the nascent shift towards the sharing economy.

Most importantly of all, it takes away the bureaucracy and shiny marketing suites and sales spiel that puts a lot of people off the conventional route.

Why are disruptors so rare in real estate?

In arguably the most important piece of literature in the study of brands, Dr Jennifer Aaker defines the big five brand personality types: ruggedness, excitement, sincerity, sophistication, and playfulness. Almost every successful brand scores high in one of these pillars, sometimes with a pinch of another. Harley Davison is rugged with a pinch of excitement. Virgin is playful with a pinch of sophistication.

But property evades categorisation every time.

Agents rarely have niche-enough listings to drill down into a set style or “brand personality”. The market is too volatile and competition too vicious for agents to pick and choose the type of property they list. 90% of real estate agents will sell a mixture of houses and flats, new and old, low-end and high-end.

It’s perhaps for this reason that many modern estate agents are self-branding. They’re harking back to the old 50’s salesman stereotype, only this time there’s branded scented candles and carefully curated Instagram feeds. We’re seeing their faces on the sides of buildings and buses and they’re making memes and TikToks about their sales prowess. They’re adopting the old-school “call me anytime, night or day – on my personal phone number” mentalities – a far cry from so many baby-aged tech firms who’ve never spoken to a customer face-to-face in their lives.

Gentle mockery aside, one of estate agents’ key strengths is that they are a true high street presence. They’re places you can still walk into and speak to a person. They keep tissue boxes under their desks and they understand their job is to hand-hold as much as to haggle. Moving house is much more emotional than calling a ride or booking a hotel. These are obvious reasons the property sales model is rooted firmly in the physical.

Another obvious and unignorable factor is that there’s no fresh-faced young consumer groups to disrupt it for. The millennial and Gen Z tribes are largely locked out of the property market. Estate agents don’t need to reorientate their strategy. They’re still selling to the same customers they had decades ago, even if this time they’re back for investments rather than homes.

There’s a huge difference between estate agents and proptech firms – locality. By the very nature of what they do, high street agents can’t go global. Their main strength is their core understanding of a local area.

Proptech on the other hand can and should be taking a global view. The key is establishing a homogenous system that can work across global house-selling markets. As platforms like Rentify and SpareRoom have shown, this is much easier in the rental market (because renting works in much the same way worldwide).

Will proptech ring in the revolution?

Proptech has affected the status quo. But you’d hardly call it a seismic shift.

Communication and administration is arguably more efficient between agents, buyers, sellers, lawyers, and builders. We can do virtual tours now. We have smart buildings where managers can dim lights and unlock doors remotely. But from an aerial view, the property industry still looks exactly the same as it did 50 years ago. And there are very few industries in 2021 that can say that.

A pitfall of proptech is that it can’t tell a truly motivated buyer from a timewaster. Real estate is rife with nosy neighbours, dreamers, and daytrippers wanting to have a mosey around houses they can’t afford and will never act on. Worse than wasting agents’ time, they waste the time of genuine sellers who spend whole days cleaning for viewings. The only vanguard against this kind of activity is human-to-human conversation where agents can question and qualify potential buyers.

In the words of Patch founder Mark Allen,

We like to make the connection between the way people used to use travel agents and stock brokers – now we use Airbnb and trade stocks on the couch. Technology is sometimes gatekept and isn’t user-led, but it always ends up disintermediating for the better.

People want simple solutions that save time and money. Real estate is just one of those industries that has been difficult to crack because it’s such a complicated thing to try to make simple for people (buying and selling a home).

There’s other industries that are similar, but people have worked out how to put the user in control and remove middlemen.

Uber forced down taxi prices, Airbnb forced down hotel prices, and Spotify basically bankrupted all other music purchasing formats. The difference is, real estate firms don’t own the houses they sell. People do. Houses are full of financial, physical, and emotional value. They’re nest eggs, inheritances, places to raise families. There’s no margin shaving, undercutting, or mass producing to be had.

Startups can’t change house prices, but they can work to change and assist the market that creates these conditions.

The goal in the meantime might just be to shift the current state of the market to something a little better than “insane”.