Are you lucky enough to have received an A for “good effort” in school?

Most students have only ever rewarded for good grades – AKA outcomes. The same goes for the history of corporate employment.

But organisations that doggedly pursue results without recognising the efforts behind them may be missing a key element.

Giving credit to employees for trying their best is a relatively new concept. It fits into Management Theory Y, which emerged in the 50s. In contrast to the whip cracking Theory X of the Henry Ford days, it posits that employees are internally motivated, trustworthy, and in fact most productive under a nurturing management style.

Dramatically increased awareness of employee mental health has led to a new theory: reward effort, not outcomes, if you want the best work out of your employees.

Life in the meat grinder

We’ve just borne witness to the tragic suicide of a 27 year old EY associate in Sydney. It’s thrown a glaring spotlight on the “toxic culture” of the Big 4 in accounting (EY, KPMG, PwC, and Deloitte), where employees are “pushed to their limits” and commonly refer to their workplace as “the meat grinder”.

Although employees are regularly expected to work late into the night, there is generally no reward for their extra efforts – financial or otherwise.

In a recent PR disaster it somehow bafflingly didn’t predict, Deloitte unveiled its pay grades for graduates. In Australia, consulting graduates start at $67,000 and audit and assurance graduates at $63,000.

Given the 12 to 14 hour days, that works out to be less than minimum wage.

The same culture pervades in tech. When Meta lost billions in ad revenue after iOS privacy settings changed to prevent user tracking, Zuckerberg attempted to “weed out underperformers”.

He reckoned that “by raising expectations and having more aggressive goals, and turning up the heat a little bit, I think some of you might just say that this place isn’t for you. And that self-selection is okay with me.”

Stanford Professor of Management Science Bob Sutton, who relevantly wrote The Asshole Survival Guide, posited this managerial stance would achieve three things: create a climate of fear, stigmatise employees who quit, and drive away potential new candidates.

Big corps like Google and Meta are notorious for having an outcomes over effort mindset.

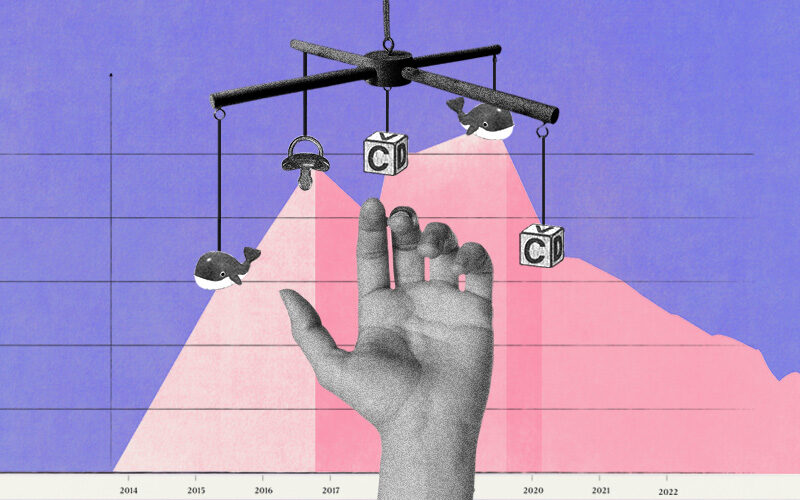

In 2004, Google employees believed any problem could be solved. It was a young, idealistic startup and hadn’t yet developed billions of users around the globe. In August 2004, Google decided to go public. Valued at USD $85 a share, its total worth hit USD $23 billion. By 2015, Google’s worth had skyrocketed 224.087% since 2004.

But what happens when a company balloons into a multi billion dollar monopoly? Less risk-taking, the rabid pursuit of continued growth, and low reward for low-probability outcomes.

Farewell to any incentive for ingenuity.

Thanks to the dizzying numbers of stakeholders and investment dollars, Google had to become results-focused. Employees weren’t rewarded for hard work which resulted in new and unexpected outcomes. Google preferred the safe route. Focus on solving pre-existing problems, and don’t take any leaps of faith.

As in accounting, there were no thank yous or well dones for staying late or taking on a colleague’s responsibilities. It was just expected.

The thing is, humans prefer decision versus force, or intrinsic rather than extrinsic motivation.

We are much more motivated to complete tasks we’ve chosen than ones we’ve been assigned. It seems obvious, and it’s also inescapable. We can’t just show up in the morning and map our own daily tasks around how we feel that day. But employers could be ignoring untapped pools of intent, creativity, and motivation.

It starts with swapping out some of the day-to-day demands with simple questions. What do you like working on best? Have you had any ideas recently? What do you feel could work better?

OKRs are (sometimes) not OK

KPIs and OKRs can help track project and company success, but they tie into employee success, where – as a very cold, tunnel-visioned metric – they don’t work so well.

They require specific goals to be followed at all times which prevents out-of-the-box thinking. It calls to mind the old invisible gorilla experiment where participants were asked to count how many times a basketball was passed between two players. Since they were so focused on the task at hand, half of them missed the giant gorilla passing the ballplayers.

When you define performance through specific outcomes, you’re limiting employees to narrow solutions. No one has time to ideate. It’s a great way to stifle efficiency and productivity.

Missing a goal or “failing” is still very triggering to many people. It can affect morale and motivation. It can lead to an imagined need for micromanagement or even disciplinary action. OKRs can even end up penalising workers for using innate ingenuity or creativity.

Asking better questions

If a software engineer spends a week writing code, but the end product doesn’t turn out as anticipated, is it the engineer’s fault? Was their time wasted? Do they still deserve to keep their job? To be paid? And what productive learnings – in lieu of punishments – can come out of the situation?

It’s also important to recognize the power of small wins. In a supportive rather than strict environment, teams can create better products overall and improve their working experience tremendously.

The employee who shows up on time and gives it their all is an employee who feels confident they’ll be appreciated.

Employees who find you unapproachable and unappreciative will also do this, out of fear. But it hardly seems the most effective way to manage.