Every decade comes with its cliches.

The eighties brought us cigar-smoking yuppies. In the nineties it was business-card-obsessed Patrick Bateman types. In the noughties it was the trainer-wearing tech nerd, and now we’re heckled by hustle culture, where if you’re not up all night running multiple side gigs and wearing “powered by caffeine” slogan t-shirts, you’re not working hard enough.

Isn’t it time we ditched the stereotypes?

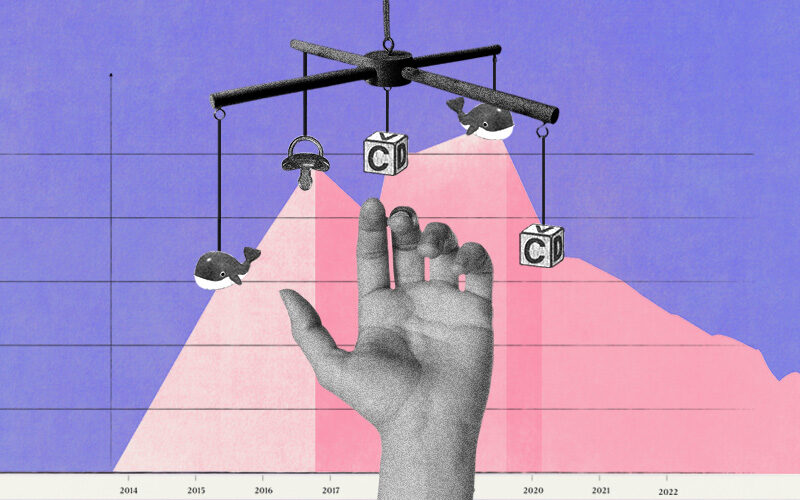

The grind economy doesn’t allow much room for family. Australians are marrying less and having families later. In some cases, it’s because they want to. In many others, it’s because they feel careerism and kids are incompatible.

Slowly over the past decade and then much more quickly following the pandemic, employees everywhere have got the memo: work isn’t everything. They shifted their focus to friends, family, physical wellness, and memorable experiences.

In many cases, they’ve taken lower paying jobs or changed fields to do so.

But, focused on that glorious acquisition or billion dollar IPO, entrepreneurs have been slower to catch on.

Can founders have it all? Or are they doomed to choose?

Founders and family

“Grind culture”, especially in entrepreneurship, has given its adopters a weird and toxic badge of honour. But the sheen is wearing off.

Take Steve Jobs. People see him as the king of kings in business innovation, and he did achieve the kind of professional greatness most can only dream of. But he was a horrible, negligent father (and person). Attached only to Apple, Jobs had no space in his life for loved ones.

Jobs is not a person we should be modelling ourselves on.

Arguably the antithesis of the Apple antichrist is Aaron Dinin. A venture-backed tech firm founder on the ascent to profitability, Dinin’s world fell apart when his newborn daughter was diagnosed with a rare genetic condition in the SADS (sudden arrhythmic death syndrome) category, and as a result of the discovery, so was he.

Dinin shut down his company to spend time with his family, fundraise for the condition, and teach entrepreneurship at Duke University. Unlike Jobs, his illness did not send him spiralling into a desperate, Big-Five-or-bust drive to leave a legacy.

Founders tend to envision their companies manifesting into a perfect world. The startup becomes the only struggle; failure the only thing that can go wrong. Caught up in tunnel-visioned ambition, founders plan only for business breakdown. Not for real-world events like illness, new babies, marriage breakdowns, or death.

In a recent trend, TikTokers have been overlaying compilations of their young children with a (love him or hate him) Jordan Peterson quote: “You have little kids for four years, and if you miss it, it’s done.”

In what seems like an almost spiritual global awakening, those plaudits we’re receiving for working hard and playing hard are tapering off.

Life won’t wait for long

In the spirit of survivorship bias, there are success stories of entrepreneurs who’ve done it all.

San Francisco based Credit Karma founder Nichole Mustard had twins while bringing in $682 million in annual revenue. It’s a happy story, but Mustard does note: “I often say, if you’re going to write a book about my life, you should just get my cell phone and see what’s been texted to me: missing the first steps or missing the first lost tooth.”

The founder of Sunrun – America’s biggest residential solar power provider – Lynn Jurich gave birth on June 13th, 2015 – 3 weeks before Sunrun’s IPO date. She brought her newborn on the 30-city investor roadshow.

Missing out on those early milestones is a trade-off many are prepared to make. After all, you could set your children up for life, paying for their degrees and house deposits. Your children could arguably benefit more than they suffer from the absence (or work ethic, depending on how you look at it) of their parents.

But if your startup takes 10 years to reach whatever point you define as success (x turnover, x customers, x valuation, acquisition), where does that leave you? Will you be 30? 40? 50? Is there a chance that without stability or steady income, you’ll miss out on too much?

Could spending your youth on the grind equate to missing pivotal experiences – by yourself, as a person, as a parent, or with friends?

In some cases, it’s just about proper delegation. In the words of Birchbox founder Katia Beauchamp, who took time off to have her baby, “Everyone wants to think that they are the most important person in an organisation but the team still thrives if you’ve done your job well. All should move forward.”

Becoming a parent doesn’t have to mean exiting the business world. It might just mean passing over the reins for a while.

Families and female founders

It’s telling that only women come up when you Google “founders who have had babies”.

With the majority of care-giving still falling to women, it’s the more notable storyline. Female founders who have families are viewed as the exception; male founders with families are seen as the norm.

Fears about telling employers about pregnancies or family plans are well known. There’s a good reason it’s illegal to ask about them in job interviews.

But investors’ reluctance to invest in pregnant founders, or even female founders of rough childbearing age, is much less talked about. Female founders already secure just 4% of venture capital in Australia – the odds are stacked against them, even before they become mothers (or are never planning to be one).

The irony is that women have long been forced to balance both, and so are arguably better equipped. The fact that they choose to invest time in their families in parallel to their careers is arguably more of a good example than a weakness.

We each have our own definition of success.

Without getting into the money/happiness debate, it’s worth stepping back every now and again to ask ourselves why we’re doing what we do.

That’s how we keep our sanity, and avoid the trap of becoming a Jobs (or a Bateman).