As with many technologies that threaten to change the world, everyone has an opinion on AI. Some are in the ‘I use Siri for everything!’ camp. And some are in the ‘AI is evil’ camp. This is mainly an article for the latter. Because if anyone can change your mind, it’s Maxus AI.

I, Robot

The cracking 2004 Will Smith film portrays a 2035 reality where humans are served by peaceful (if slightly unsettling) robot servants. The climax comes when the robot Sunny develops autonomy and breaks Asimov’s Second Law of Robotics: “A robot must obey the orders given to it by human beings”.

We’re only 13 years away from this predicted reality, and the closest we’ve come to everyday human/robot interactions is people bonding with their roombas.

In fact, that’s not quite true – we interact with robots hourly, they’re just not humanoid. Google Maps uses AI to predict traffic movement. Uber uses it to estimate wait time. Netflix uses it to recommend you new shows. Then we have the more obvious tools like Face ID, Alexa, Google Home, and park assist. It seems like AI brings us humdrum convenience and targeted advertising at best, and scary dystopian military use cases at worst.

The reality of Artificial Intelligence is a far cry from what it meant when it was coined in the 1950s. But the scope for it is far greater than anything we could have imagined.

Maxus AI: AI for human good

Maxus AI founder Glenn Neuber can think of a particularly meaningful example. Unlike the naked eye of even the most experienced doctors and radiologists, AI can learn to detect microscopic changes in human tissue before it turns cancerous. The main question is: how is remarkable capability applied across industries and subject matter experts?

Glenn’s background is varied and colourful. Born in Germany, he studied Business Administration and Corporate Finance in Italy, moving to Australia to intern at SAP’s Research department, which later became part of their Innovation Centre network. He saw the evolution from business process management to mobile business apps, then to SaaS and Cloud in 2010. From there, he saw the shift to in-memory databases, big data analytics and predictive data analytics, all leading to in-machine learning by 2016.

When SAP restructured in 2019, Glenn took his passion for large data acquisition and preparation (which he always felt lacked a certain harmony) and machine-learning to build Maxus AI.

A starring seller of this nascent technology is saving human cost. Maxus AI can assess aerial footage (think drones and helicopters) from erosion-prone regions. For instance, it can detect where silt is being washed away around the Great Barrier Reef. It can comb through aerial photography to survey critical infrastructure. This way, it can pick out the corrosion of nuts or bolts and even damage from natural disasters.

Resurrecting Aboriginal rock art

We sat down with Glenn about the Aboriginal rock art project he was connected with via a Queensland Government grant program, led by KJR.

To paint a picture, imagine a vast area of Australian bush, absent from people, in the northern part of Queensland. This is the Kuku Yalanji territory, a place holding rich Aboriginal history spanning over 20,000 years. The culture is echoed in the cliffs through ancient rock art, some of which has yet to be rediscovered. Glenn explains:

Our role is to go there and inspect the locations for potential cultural significance. We identify landmarks that would potentially show where people used to live. For example, natural overhangs or near something renewable like water.

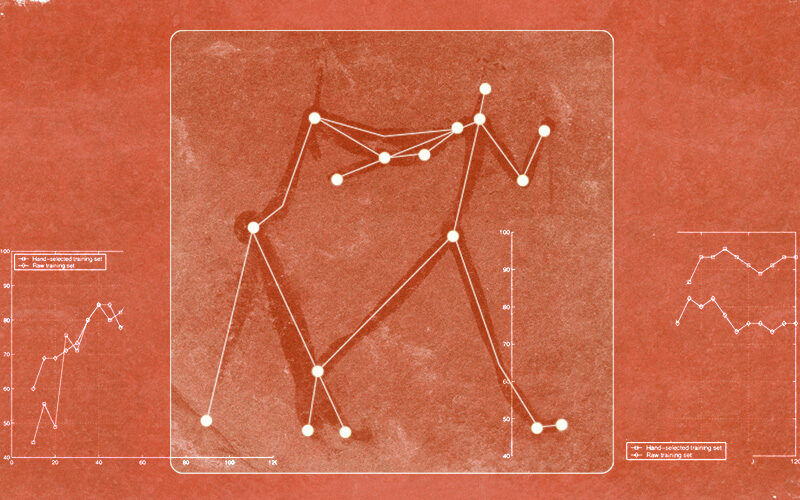

Flying drones would scout the area to identify these surfaces, which is filmed. The AI would then work its magic on hours-worth of footage to flag potential sites for rock art. Once identified, the rock art would be catalogued via AI, generating a map of classifications and labels based on cultural significance.

According to Glenn, one of the digital archaeologists on the project estimates that those AI classifications and labels developed for the Magnificent Gallery in North Queensland could potentially applied to about 80% of all Rock Art in Australia.

Closely involved in this project, Johnny Murison, one of the Traditional Owners, observes that AI can help reactivate the traditional knowledge values of his people.

Technology has taken our children away from our community and our culture. This way, we can use it to bring our young people back.

What can AI do for AU?

In Australia, land and asset-heavy industries are still such a huge part of the economy. This means that this tech has huge scope. AI is being explored in mining, oil, gas, agriculture and land management. Any industry that requires aerial inspection of land can benefit hugely from this.

In layman’s terms, as a user, you input raw images and videos into the platform. Maxus AI helps the subject matter expert in marking up each pixel they’d want the AI to learn from. That markup defines not just the object, but also the state of the object.

It’s not “here is a screw”, it’s “here is a cap hexagon socket with X level of corrosion”. Users are not required to manually mask or extract all objects from the imagery, the AI technology assists with “the cutting out” itself.

The next step is developing the neural network, which we’re already familiar with. Think Google Maps or your iPhone’s camera roll. You can search for elements in your photos, and your phone knows exactly what to present back to you.

This all boils down to AI’s interaction with data points and the subsequent intelligence it gains. As Glenn puts it:

It’s your student. That’s why we say we teach AI. It learns, we teach. Unlike with human apprentices, it’s not getting bored.

Of course there are obstacles. In Glenn’s words, “There are questions like ‘Who has access to the API?’ or ‘who can see it and who should use it?’ which have implications on the adoption of AI. We’re working hard to get it in the hands of everyone. But when moving to widespread adoption, there can be a lot of the technical hurdles.

Warming up to AI

“We’re working hard to get it in the hands of everyone. But when moving to widespread adoption, there can be a lot of technical and also ‘human’ hurdles.”

Of course there are obstacles. Some times they manifest as legal questions, like ‘who owns the IP?’ or ‘who is responsible if the AI makes a mistake?’. According to Glenn, these have implications on the adoption of AI.

“We are not trying to force the user to upload all their data to our platform. It’s not helping businesses to try and adopt AI quickly because often one needs approvals to share data with third parties.”

“With us, our browser app works with local data, we only store and sync your manual labelling work with a fingerprint of your images or videos in our database. This allows us to keep our clients’ data secure within their corporate network but also to collaborate.”

In this way, AI works with data and not against it. People can bring their own data buckets like Amazon S3, which Maxus AI can integrate. They can work on the platform without it storing everything in one central place.

The work that Maxus AI and its contemporaries have done is undeniably good for humanity. But it doesn’t mean concerns around AI are unwarranted.

Isaac Asimov, author of the original I, Robot novel, based his plot around Three Laws Of Robotics:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

But if robots are being used in military technology, the first law can’t stand. If the second law stood, the enemy could simply politely command an attacking drone to stop. The only one that really holds its weight today is the third. But the third can’t exist without the first two. And those are some scary implications.

AI-utilising companies must prove they are safeguarding privacy and using data responsibly (i.e. not profiteering off it). Otherwise the more they use AI to underpin their operations, the more likely their reputation will end up even worse than modern-day Will Smith.